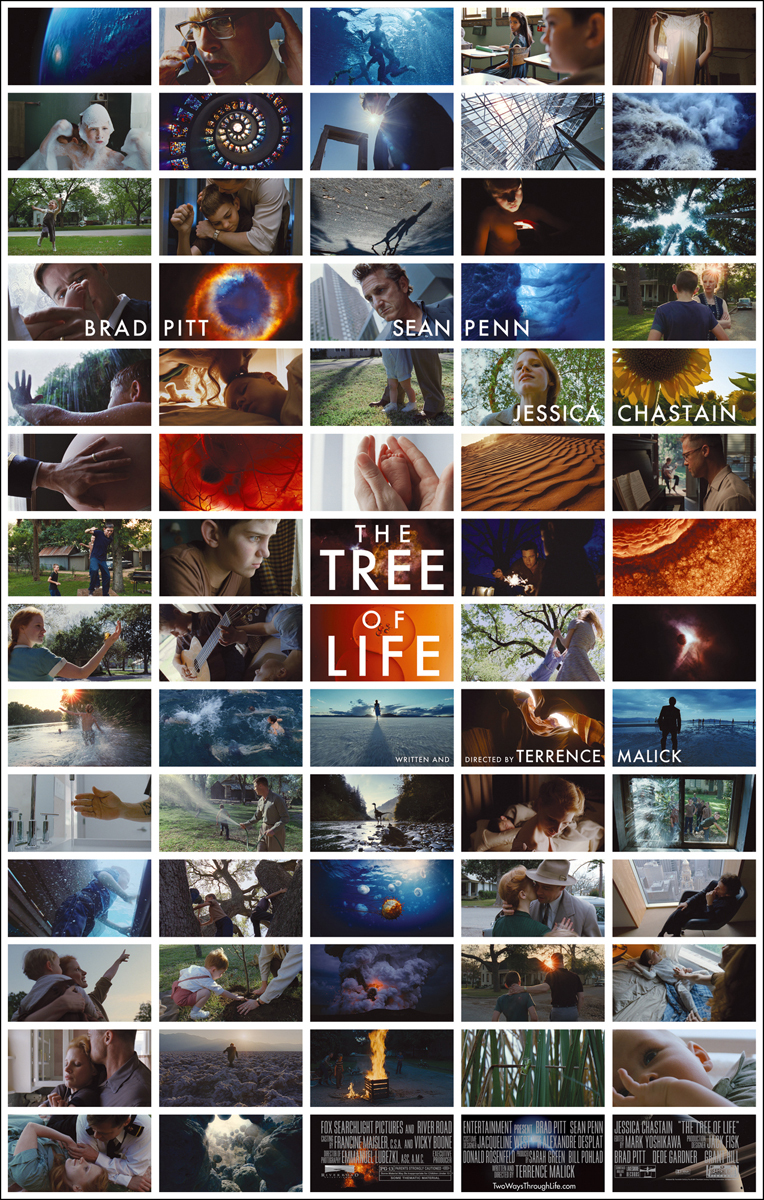

Terrance Malick’s Tree of Life is a film founded on immense contradiction. It is at once vast and yet intimate, loud and yet quiet, poetic yet human, spiritual yet scientific and ultimately concludes with maybe the only truth that we can ever really know: that life, existence, the world, the universe, everything, is itself founded on contradiction. Without hot is no cold, without day is no night and vice versa on until time runs out. No matter what wall one comes upon on their journey to whatever, they are always at the mercy of the antithesis and the only way to know what is right, not in some grand finite way, but rather a personal, individual way, is to grow and change through experience. That's what Tree of Life shows. Simply put, it is a masterpiece.

The next logical thing to do would be provide a description of the story. But how can one even begin? Anyone who is familiar with Malick’s work knows that he is a filmmaker who feels stories as opposed to telling them. His films, for the most part, are a colleague of images and words, jagged angles and beautiful points of view. To attempt to describe them is to back them into a corner and label them as a standard routine in which a story follows itself from a beginning to an end. That’s not what Malick does. Like a poem, his films create feelings through the way they link ideas and images together to create some sort of higher meaning that, this time out, boarders on the profound.

I’ll try my best here. The film opens with Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien (Brad Pitt & Jessica Chastain) receiving word that one of their sons has died. The film then jolts us back to the very beginning of time as images of barren landscapes shrouded by majestic colours swirl around together. Fire erupts, oceans begin to flow, and dinosaurs walk the Earth and begin to take on human instincts. Evolution is in progress.

In the city is Jack, played by Sean Penn, the son of the O’Brien’s, now grown up and an architect. In a way that is more implied at this juncture of the story, Jack is in the midst of a spiritual crisis. He has found success as an architect but high above all the steel and glass he still sees God’s blue sky and amidst the concrete is His grass and trees.

The film then jumps back to when Jack is a boy growing up in small town America under his parents with his brothers, learning life lessons, rebelling, falling in line and genuinely feeling his way through life one success and mistake at a time.

Near the opening of the film Mrs. O’Brien is heard in voice over explaining that there are two ways to live your life. One of them is with grace because grace doesn’t care and doesn’t aim to please anyone; it can meld itself in any way in such that one is always at peace. The other way is through nature which is sturdy and rigid, never satisfied and always looking to better itself and find praise from others.

The initial suspicion is that O’Brien is talking about the difference between God and nature, claiming God to be all that is good. In time it can be interpreted that this is declaration is a reflection of the roles that each parent plays in Jack's shaping, who, to continue, each take on a form of our belief in God as both the ever loving creator and the remorseless punisher. However the film does not push God above nature or God the punisher above God the protector but delicately shows, over the course and two and half meditative hours, that, like everything, when blended together they shape and define an entire life, leaving Jack to declare “Mother, Father, you will forever wrestle inside of me.”

Over the course of the film we see Mrs. O’Brien being the loving Sheppard, tending to her flock, encouraging them to look to the sky and see God’s home. While Mr. O’Brien loves his family he is also hard working and believes in tough love in order to persuade his boys to grow up to be hard working men who can make a living and a name for themselves. In yet another contraction the film begins and ends with a spiritual crisis of both parents, realizing that to be defined by just grace or just nature is fruitless and will always leave oneself unsatisfied as only half a life will be lived.

The conclusion of the film takes place in what may as well be considered, for poetic reasons, Heaven. Here Jack finally realizes that he need not be defined by either Nature or Grace, mother or father, God or not, but that the definition in his life is created through all those who have passed through it and what their perspectives have taught him. The closing images of the film, including one of the most startlingly beautiful, shows a changed perspective in which Grace and nature have come together.

Roger Ebert has described Tree of Life as being like a prayer and that’s about right. It follows no conventional structure on the path to creating a personal link between a boy and God or, better yet, a boy and himself, which, depending on your religious belief, is the same thing. I use God for lack of a better word and because the film refers to Him as God, yet one needn’t be thrown off by such interpretations. This is a deeply spiritual film, not a religious one.

It is rare in this day and age that a film be so ambitious and so dedicated to exploring its own concepts in the way in which it chooses. Terrance Malick has been active in the film world for almost 40 years and has only delivered five feature length releases. His films are not for every one. Like a poem they require quiet reflection as their interpretation will be based on how the viewer engages with the images before them. But those who will afford it their time and patience will find themselves renewed by it. In a age of film where personality and singularity of vision doesn’t seem to be worth much anymore, Tree of Life is one of the last few movies we can justifiably call a masterpiece. It is a work to be embraced and savoured

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Retro Review Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen

The late Gene Siskel used to say that a movie needed to be more interesting than a documentary about its actors having lunch. Now, in 2009, a new method of thinking is needed. A movie needs to be better than playing a video game based on the same material. Or, how about one just for Transformers? A movie needs to be better than playing with the toys that it is based on. Take your pick. The moral of the story is that Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen isn’t much more than a video game minus the interaction. It is a big, loud, stupid, uninvolving, empty movie in which the action sequence reins supreme and all else is subordinate to it. It's the kind of movie that, if not firing on all cylinders, isn’t firing at all.

What’s left is a head-on collision of non-stop special effects and pyrotechnics, aesthetically comparable to a train wreck with about the same amount of emotional and intellectual depth. You could cut every character scene out of the film and wouldn’t lose much. Come to think of it, you could cut any whole section out and would be no worse off. Not a good sign at two and a half hours of running time. Allegedly the screenwriters on the film (three of them) were paid 8 million dollars for their work. Times must really be tough if, or so it would seem, 8 million barely gets a screenplay out of the planning stages.

This, under the obsessive, excessive hand of sometimes great action filmmaker Michael Bay is not filmmaking. It is instead an exercise in physical, mental and intellectual endurance, created in order to satisfy the narrow minds that need as many visual jolts as there are frames per second. A film built, not from artistry, but to fill a demand for faces to put on t-shirts, and coffee mugs and lip balm, and so on; to sell soundtracks and special editions of DVDs and toys. Who needs a story, or characters, or even coherence for that matter, when you have tie-ins?

So the story: Why bother? There is no story here, there is barely even a script, and what’s there is buried so deep amid piles of useless action that it ceases to be comprehensible. It's something about the evil Decepticons wanting to destroy the sun maybe? There is a certain point where, when assaulted endlessly, the senses simply shut down and cease to decipher what is going on. Revenge of the Fallen is a two and a half hour blur of noise and colour.

But now, isn’t this stupid, after the events of the first film, the humans and the Autobots have formed a coalition to protect Earth from Decepticon attacks. This is kind of funny considering how infantile the humans and their weapons were against the Decepticons the first time around. Why are the humans even in the film? All this proves is how useless their presence actually is to the Transformers franchise. Their three possible functions are: fire ceaseless rounds of ammunition to no avail. deliver bad sitcom punch lines or run away from expositions. Sometimes, during particularly ambitious moments, they do all three at once.

The humans are played by Shia Lebouf who is working below his rank when he deserves the kind of fast, intelligent roles James Woods used to get and Megan Fox, the extent of whose talent as an actress is pretty much summed up during the first scene she appears in here. These characters contribute nothing to the already non-existent plot, but are along for the ride out of default: they were part of the first film. But really, any human character could have been played by any actor and it wouldn’t have made any difference.

Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen is too big, too bloated, and too ambitious for its own good. It doesn’t stop to breathe, to develop its characters or at least give reason why they even need to be present in the first place, and doesn’t have time enough to at least create Transformers for us to care about. Think about it. The robots really aren’t that interesting. On their own, only about 5 or 6 of the dozen plus have discernible personalities and when engaged in battle they are simply a smear of spare parts, welded together in combat that flashes by so quickly that the eye can barely focus on it before it’s gone.

To top it all off, the film itself is just sloppily made with some scenes throwing continuity between edits right out the window. What was fun the last time around now feels like a bloated, lazy over-indulgence. It's as if Transformers has become such a huge franchise that fans wouldn’t even care if the film was made well as long as things blew up real real good.

There is, however, one very entertaining moment in the film, possibility providing an example of the problem with all of the human elements of Revenge of the Fallen. After the Witwicky home is overcome by Transformers made out of common household appliances, the Autobot, Bumblebee, who is hiding in the garage, comes to the rescue and shoots half the house to smithereens. After the incident, one of the characters talks about how they can’t tell anybody about what happened because the Transformers must be kept secret for the benefit of national security. Forget national security. If you live in the suburbs and don’t notice a giant robot Camaro blowing away half your neighbor’s house in one swift move you may be deaf, dumb and blind, or else are in a Michael Bay movie.

Retro Review: Transformers or Is Michael Bay a Great Director After All?

I once saw Martin Lawrence a few years back on the Conan O’Brien show promoting his then new film Bad Boys 2. As is usual, a clip from the film was played, this one showing Lawrence and co-star Will Smith engaged in a high speed chase over a bridge, destroying everything in their path. When the clip ended O’Brien gave positive feedback and Lawrence’s exact response was “That’s the genius of Michael Bay.” I scoffed, Michael Bay a genius? Lawrence was feeding us a line.

I was not among the minority when I denied Michael Bay the right to genius so many years ago. The director has been bombarded by fans and critics alike with every negative adjective imaginable. The man has been called a hack, a sexist, a racist, a fascist dictator, incompetent, etc. Does Bay deserve this, I must ask? Certainly he has made duds (Armageddon, Pearl Harbor), but why do film goers insist on the continual burning of effigies at the alter of Michael Bay, as though he is the antithesis of everything that is good about the cinema? It’s as if the man has single handedly lowered the collective I.Q. of every being who has ever sat in front of one of his films. Do these films really have the same kind of sway that Mites and his magical touch did or something?

The question then is, is Bay a great director? I now understand what “genius” Martin Lawrence was talking about. In an interview, Bay once said that he tells his writers that whenever they want an action sequence just write “Blow Stuff Up” on the page and he will fill in the blanks. Although joking, this single statement unlocks all of the excitement and deficiencies of the cinema of Michael Bay. Unless he is given characters that are already defined and a plot that will be able to sort itself out, Bay finds himself lost in the ruins of his own excesses. However, Bay is not a filmmaker so much as he is a painter of spectacles. Write Bay a film that provides enough cushioning to hold our interest between his relentless bouts of blowing everything in sight up real good and the man is second to none. Sometimes that’s all genius takes. After all, what more could one really desire from a film about robots from outer space who have come to destroy us?

And herein is where interests begin to conflict. Michael Bay is both the best and worst director for this material. The film’s greatest asset is also its biggest detractor: that is, it’s one, big, long, never ending action sequence stretched out over the unruly span of two and a half hours.

The action is fantastic: big, loud, imaginative, exciting, never-ending and incredibly detailed. Bay went to great pains to incorporate the real with the computer generated. But the man has no control. He just doesn’t know when to stop. The entire screenplay must have been comprised solely of Bay’s three favorite words: Blow Stuff Up. There are no characters in this film, no room for actors to give performances as Bay relies, as he always does, on the simple screen presence of his stars, who are forced to go way over the top and then keep going. Every character scene is filmed with the bang-boom-slap-bang mentality of an intense action sequence. It’s great that Bay doesn’t want to lose momentum but there’s not one opening to catch a breath in the whole damned thing. If Transformers were a fish, it would drown. That’s the contradiction: it left me with a surge of excitement and a headache.

The plot, as many probably know, is based on a popular cartoon series and toy line from the 1980s in which good Transformers (Autobots) battled evil ones (Decipticons). Of course, my nostalgia over playing with Transformers as a child far outweighs the memories of actual enjoyment that the toys provided. They were clumsy and awkward, sometimes hard to transform. This of course being all undermined by the shadow of intrigue created from getting two toys for the price of one.

The film is like this too. It’s clumsy and awkward, illogical at times (if Disturbia had any thread of realism, someone would notice a transport truck and a couple million dollars worth of cars driving through the suburbs at night, would they not?), which is undermined by how exciting and action packed it is while we play. That’s the genius of Michael Bay that Martin Lawrence was talking about: to accept the illogical and make it as spectacular as possible.

Esteemed critic and film historian David Thompson once said that Stanley Kubrick knew everything about filmmaking but nothing about life. Michael Bay is kind of the same: he knows everything about action, but nothing about humanity. His films destroy everything in their sights while never even considering the many people who have lost their homes or are out of jobs because of the trail of destruction caused by the warring Transformers. Bay doesn’t care about characters who deliver sitcom jokes and soap opera melodrama at a rate that even an ADD sufferer would find excessive, he waves the American flag (quite annoyingly) at every chance he gets and destroys so much property that one almost feels urged to have him brought up on charges of assault to the senses. So much so in fact, that when Optimus Prime as a transport truck, rolls out of an alleyway during the film’s climax, knocking stacks of crates and boxes out of the way, I thought to myself: Now, that’s just excessive.

Monday, June 13, 2011

The Celebrity Connection - Justin Beiber

I just happened to catch a picture of Justin Bieber at the MTV Movie Awards, accepting an award for something (I don`t know because I couldn`t be bothered to watch) and it struck me that the mini prima dona, who shot to fame for reasons that have everything to do with anything but talent, is sporting a new look that looks remarkably like another former child star has-been:

Could Justin Bieber really just be Corey Haim in disguise. You decide.

Could Justin Bieber really just be Corey Haim in disguise. You decide.

Labels:

Corey Haim,

Justin Beiber,

The Celebrity Connection

The Hangover Part 2

When a run ragged Bradley Cooper appeared in the first scene of The Hangover, in the middle of the desert on a cell phone telling someone on the other end how he had seriously F.U.’d it was one of the great comedy set-ups. He wasn’t kidding and, with giddy delight we were going to see just how. When Cooper appears in the first scene of the sequel to say he seriously F.U.’d again it feels like we’ve already been there and seen that. The premise is the same but the shock and intrigue is missing.

Not that director Todd Phillips and his team don’t try to keep the shocks coming but that’s just another one of the problems: most of what is memorable in The Hangover 2 is not how quick and hilarious it is, but just how far it is willing to push the boundaries of good taste for a laugh. But the laughs are few and far between, being undermined by the gross and absurd. It’s like Phillips forgot that the premise is the set-up not the punch line this time around.

What made the first film special above all else was that, although set in Las Vegas, it seemed to take place in a surreal parallel world in which a bunch of random objects came together and all fit in such a way that made perfect sense. It was darn near Kafkaesque. This time the boys find themselves in Bangkok and although everything makes sense again this time it’s not as inspired in it’s madcap schizophrenic way. By the time the film has been reduced to high speed chases away from Russian gangsters and crooked business men one gets the sense that we are looking at a film having fallen to the everything in the sequel needs to be the same but amplified school of thought.

This time out Stu (Ed Helms) is getting married in his fiancée's native Thailand. Phil (Bradley Cooper) and Doug (Justin Bartha) are invited as well as, after some pleading from Doug, Alan (Zach Galifianakas) who hasn’t stopped talking about Vegas and has pictures from that trip that probably shouldn’t have been published let alone be allowed to hang from his bedroom walls.

Also along is Stu’s brother-in-law to be, the 16 year old Teddy. The boys decide to have one drink on the beach the night before the wedding, thinking nothing could possibly happen. Then they wake up in a grungy hotel in Bangkok with a monkey, no sign of Teddy and Mr. Chow (Ken Jeong) the Asian gangster from the first film. Chow, knowing what happened to Teddy, is about to spill the beans before taking a hit of coke so big that it kills him. So they ditch the body and begin their search.

Their journey brings them into contact with a mute monk, a tattoo artist played by Nick Cassavettes which is surprisingly mild for a cameo role, a drug dealing monkey, and a club that Alan hilariously mistakes as a magic show.

Some of this is, for what it’s worth, quite funny. But it’s not enough. The movie, like the first one, pushes boundaries, doesn’t care who it is offending and will gleefully go anywhere it needs to for a laugh even at the expense of alienating just about everyone in the audience. I admired that quality the first time around as well and although Phillips has turned in a well made film, and the actors have all done their work, something just isn’t clicking. The magic of going on this journey and solving this mystery is gone this time around. The pieces are all in place but they don’t build a new enough puzzle.

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

One Minutes Review - Flipped

One of my favourite things in the movies is nostalgia. I love the idea of a simpler time where kids were sweeter and more innocent. Where you could trust your neighbour and appreciate the simple things like touching hands with the boy across the way, weeding the front lawn and climbing the old sycamore tree to take in the view from the top. And of course there was grandpa who wasn't old and senile but tender, loving and always knew how to bring all the problems together and set them back on the right foot.

I also love that moment between childhood and adolescence where nothing makes sense, everything isn't as how you imaged it to be and the only way to grow up and get on with life is to make the stupid mistakes and then reflect back; hoping you learned something and didn't do irrevocable damage.

Flipped, Rob Reiner's best film is over ten years, has all of these things. It's a beautiful postcard to the early 60s, and a sweet tale of two kids who live across the street from each other. One is Juli Baker (Madeline Carol) who is desperately in love with Bryce Loski (Callan McAuliffe) from the moment his family moves in across the street. They are both young and while playing their hands connect for a brief moment, more or less sealing their fate.

Grown up into adolescence, Bryce wants nothing but for Juli to leave him alone. His family is upper class, his father, subtly suggested to resort to the booze to make up for a missed life as a musician, is cold and demeaning while Juli's family is poor but full of love and are judged by the state of their front yard. Her father is an aspiring painter which also is greeted with scoffs across the street.

This goes on until, as events must transpire, Bryce realizes that he really likes Juli while Juli slowly realizes maybe Bryce wasn't what she had envisioned after all. This is all told in voice over as the same events are flip-flopped back and forth to be told first from Bryce's point of view and then Juli's.

And holding everything together is Grandpa (the invaluable John Mahoney) who has moved in with Bryce and who is kind, knowing and misses grandma.

All of this is sweet and innocent and doesn't hurt anyone. It takes place in a whimsical movie land which once doubled as America but now, all these years later, seems like a distant fantasy. It's exactly the kind of movie that makes you sit back, smile and remember the days when things were both so simple and yet so complicated all at once. The best days, some may argue, of our lives.

I also love that moment between childhood and adolescence where nothing makes sense, everything isn't as how you imaged it to be and the only way to grow up and get on with life is to make the stupid mistakes and then reflect back; hoping you learned something and didn't do irrevocable damage.

Flipped, Rob Reiner's best film is over ten years, has all of these things. It's a beautiful postcard to the early 60s, and a sweet tale of two kids who live across the street from each other. One is Juli Baker (Madeline Carol) who is desperately in love with Bryce Loski (Callan McAuliffe) from the moment his family moves in across the street. They are both young and while playing their hands connect for a brief moment, more or less sealing their fate.

Grown up into adolescence, Bryce wants nothing but for Juli to leave him alone. His family is upper class, his father, subtly suggested to resort to the booze to make up for a missed life as a musician, is cold and demeaning while Juli's family is poor but full of love and are judged by the state of their front yard. Her father is an aspiring painter which also is greeted with scoffs across the street.

This goes on until, as events must transpire, Bryce realizes that he really likes Juli while Juli slowly realizes maybe Bryce wasn't what she had envisioned after all. This is all told in voice over as the same events are flip-flopped back and forth to be told first from Bryce's point of view and then Juli's.

And holding everything together is Grandpa (the invaluable John Mahoney) who has moved in with Bryce and who is kind, knowing and misses grandma.

All of this is sweet and innocent and doesn't hurt anyone. It takes place in a whimsical movie land which once doubled as America but now, all these years later, seems like a distant fantasy. It's exactly the kind of movie that makes you sit back, smile and remember the days when things were both so simple and yet so complicated all at once. The best days, some may argue, of our lives.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)