Sorority Row is a real howler. In the third act, after it is believed that one of their sorority sister's who was killed in the midst of a nasty prank has come back from the dead to pick the remaining girls off one by one, the house's head mistress (Carrie Fischer) shows up unexpectedly with a shotgun to find the house in ruins after it is terrorized by the cloaked murdered. One of the girls accidentally lets it slip that they were responsible for the death of their missing sister. Instead of being baffled, shocked, taken aback, disgusted, anything that a normal person would do when faced with such information, the mistress racks the barrel and declares that whoever he/she/it is, it's about to get two to the face. Then, when but a few survivors remain and the killer's identity is revealed, one of the still living girls bashes the killer over the head with an inanimate object and runs away before checking if they are dead not once, but twice in the span of minutes. Shouldn't every horror movie character know by now that unless you physically see to the death of a demented killer, giving them a good whack or two usually doesn't solve much?

It's been quite some time since a film was as heedlessly careless with it's audience's intelligence as Sorority Row is. Not that horror movies have never been dumb or anything, but ever since Hollywood started remaking every Japanese horror movie in sight or got all involved with movies about torture, they've been relatively straightforward, ugly and humourless. How rare it is to see one so lazily phoned in? Finally we get another horror film that no one asked for, that had no chance of being seen by anyone but horror fans and that couldn't care less that it's about as stupid as anything out there. It's nice to see that, in these economic times, Hollywood still has it in itself to throw money away for ol' times sake.

That's it. The girls are stupid and not overly attractive. They are also vain, shallow and unlikable. Think of Sex and the City as a slasher movie. And they also go through all the old standbys of running up the stairs when they should be running out the front door. Oh ya and when they go back to the mine shaft that they dumped the murdered girl's body down they find the dude there who was the one who actually killed her because, of course, he's probably been waiting there all year since for the moment when they would return. That makes sense.

Sorority Row is a real howler. In the third act, after it is believed that one of their sorority sister's who was killed in the midst of a nasty prank has come back from the dead to pick the remaining girls off one by one, the house's head mistress (Carrie Fischer) shows up unexpectedly with a shotgun to find the house in ruins after it is terrorized by the cloaked murdered. One of the girls accidentally lets it slip that they were responsible for the death of their missing sister. Instead of being baffled, shocked, taken aback, disgusted, anything that a normal person would do when faced with such information, the mistress racks the barrel and declares that whoever he/she/it is, it's about to get two to the face. Then, when but a few survivors remain and the killer's identity is revealed, one of the still living girls bashes the killer over the head with an inanimate object and runs away before checking if they are dead not once, but twice in the span of minutes. Shouldn't every horror movie character know by now that unless you physically see to the death of a demented killer, giving them a good whack or two usually doesn't solve much?

It's been quite some time since a film was as heedlessly careless with it's audience's intelligence as Sorority Row is. Not that horror movies have never been dumb or anything, but ever since Hollywood started remaking every Japanese horror movie in sight or got all involved with movies about torture, they've been relatively straightforward, ugly and humourless. How rare it is to see one so lazily phoned in? Finally we get another horror film that no one asked for, that had no chance of being seen by anyone but horror fans and that couldn't care less that it's about as stupid as anything out there. It's nice to see that, in these economic times, Hollywood still has it in itself to throw money away for ol' times sake.

That's it. The girls are stupid and not overly attractive. They are also vain, shallow and unlikable. Think of Sex and the City as a slasher movie. And they also go through all the old standbys of running up the stairs when they should be running out the front door. Oh ya and when they go back to the mine shaft that they dumped the murdered girl's body down they find the dude there who was the one who actually killed her because, of course, he's probably been waiting there all year since for the moment when they would return. That makes sense.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

One Minutes Review: Sorority Row

Sorority Row is a real howler. In the third act, after it is believed that one of their sorority sister's who was killed in the midst of a nasty prank has come back from the dead to pick the remaining girls off one by one, the house's head mistress (Carrie Fischer) shows up unexpectedly with a shotgun to find the house in ruins after it is terrorized by the cloaked murdered. One of the girls accidentally lets it slip that they were responsible for the death of their missing sister. Instead of being baffled, shocked, taken aback, disgusted, anything that a normal person would do when faced with such information, the mistress racks the barrel and declares that whoever he/she/it is, it's about to get two to the face. Then, when but a few survivors remain and the killer's identity is revealed, one of the still living girls bashes the killer over the head with an inanimate object and runs away before checking if they are dead not once, but twice in the span of minutes. Shouldn't every horror movie character know by now that unless you physically see to the death of a demented killer, giving them a good whack or two usually doesn't solve much?

It's been quite some time since a film was as heedlessly careless with it's audience's intelligence as Sorority Row is. Not that horror movies have never been dumb or anything, but ever since Hollywood started remaking every Japanese horror movie in sight or got all involved with movies about torture, they've been relatively straightforward, ugly and humourless. How rare it is to see one so lazily phoned in? Finally we get another horror film that no one asked for, that had no chance of being seen by anyone but horror fans and that couldn't care less that it's about as stupid as anything out there. It's nice to see that, in these economic times, Hollywood still has it in itself to throw money away for ol' times sake.

That's it. The girls are stupid and not overly attractive. They are also vain, shallow and unlikable. Think of Sex and the City as a slasher movie. And they also go through all the old standbys of running up the stairs when they should be running out the front door. Oh ya and when they go back to the mine shaft that they dumped the murdered girl's body down they find the dude there who was the one who actually killed her because, of course, he's probably been waiting there all year since for the moment when they would return. That makes sense.

Sorority Row is a real howler. In the third act, after it is believed that one of their sorority sister's who was killed in the midst of a nasty prank has come back from the dead to pick the remaining girls off one by one, the house's head mistress (Carrie Fischer) shows up unexpectedly with a shotgun to find the house in ruins after it is terrorized by the cloaked murdered. One of the girls accidentally lets it slip that they were responsible for the death of their missing sister. Instead of being baffled, shocked, taken aback, disgusted, anything that a normal person would do when faced with such information, the mistress racks the barrel and declares that whoever he/she/it is, it's about to get two to the face. Then, when but a few survivors remain and the killer's identity is revealed, one of the still living girls bashes the killer over the head with an inanimate object and runs away before checking if they are dead not once, but twice in the span of minutes. Shouldn't every horror movie character know by now that unless you physically see to the death of a demented killer, giving them a good whack or two usually doesn't solve much?

It's been quite some time since a film was as heedlessly careless with it's audience's intelligence as Sorority Row is. Not that horror movies have never been dumb or anything, but ever since Hollywood started remaking every Japanese horror movie in sight or got all involved with movies about torture, they've been relatively straightforward, ugly and humourless. How rare it is to see one so lazily phoned in? Finally we get another horror film that no one asked for, that had no chance of being seen by anyone but horror fans and that couldn't care less that it's about as stupid as anything out there. It's nice to see that, in these economic times, Hollywood still has it in itself to throw money away for ol' times sake.

That's it. The girls are stupid and not overly attractive. They are also vain, shallow and unlikable. Think of Sex and the City as a slasher movie. And they also go through all the old standbys of running up the stairs when they should be running out the front door. Oh ya and when they go back to the mine shaft that they dumped the murdered girl's body down they find the dude there who was the one who actually killed her because, of course, he's probably been waiting there all year since for the moment when they would return. That makes sense.

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

The Remake/Sequel/Reboot Debate

Because Kid in the Front Row always seems to do it first and best (no wonder he doesn't like remakes) he's started a one day blogathon in which bloggers were invited to weigh in with their thoughts on remakes, sequels and reboots. Of course, never wanting to miss the chance to chime in and always happy to have content given to me, here's my take.

It's easy these days to throw Hollywood under the bus and call them creatively bankrupt because it seems that they will remake, reboot and make a sequel to just about anything they can get their hands on. That's the current state of mainstream cinema. We've seen it all summer and it extends out into the peripherals of the entire year as well. However, because this is the current state of cinema, it's what we are left to deal with. We could sit here and argue all day that Hollywood needs to turn it around, find original content, and so on. That is, of course, ideal but to do so is to think about what we want as opposed to deal with what we have. You end up missing a lot of good movies that way.

Personally I am fine with remakes/sequels/reboots. I am fine with it not because I want to see other versions of films I've already seen but because a good film by any other name...as Shakespeare once wrote. If a sequel is well made, than who cares what source it was derived from? And where is it written in stone that al movies based on original content will automatically be good? We spend so much time these days concerned with everything surrounding a movie from it's origins; the tabloid exploits of its players; how much money it made or lost; how good the original was; how this should never have been remade; how stupid Hollywood is, etc., that we almost forget that the film is what is most important: story, characters, acting, direction, editing, lighting, cinematography and how all of these things collide into one another to make magic. That's what's important, everything else is gravy.

And sequels/remakes/reboots, taken as an original concept and not a current fad, also serve a very specific purpose. Godard once said that the best way to criticise a film is to make another. So why not remake a bad movie, or take a different approach, start again from scratch, whatever? The reality of it is that, depending on the circumstances, it will either work or it won't. But that's the same for original films as well. Godard's Breathless was remade in Hollywood and didn't work. You can't take a film that defined a generation with it's originality and invention and make it into a standard Hollywood drama. However, when Sergio Leone used Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, almost line-for-line, as the inspiration for his Fistfull of Dollars, a whole new genre was born. The difference was that Breathless took the story and simply put it back on film. Leone on the other hand, took Yojimbo and made it his own. That's the success of a remake. That's the success of any film, no matter the source.

And really, what defines an original film? Even original films are rarely ever true originals, and when they are, we sometimes never even hear of them. But just look at some of the past year's original works: Crazy Heart was The Wrestler meets Tender Mercies; Avatar was every classic American western and even Inception was just made up of pieces of every previous Christopher Nolan fil; The Prestige in particular. The definition of an original film is that it wasn't adapted from any existing source, but the idea or true originality usually stops there. History is destined to repeat itself. Hollywood just gets around to it faster than most.

So, do I want to see great films remade? No, but hey, if someone needs to take a little from Hidden Fortress to make a Star Wars, I'm okay with that. And if it takes three decent movies to get to the best Jason Bourne one, I'm okay with that too. Ideally Hollywood would only remake or reboot bad movies with the intention of making them better. But again, we're speaking in ideals and missing the point: if the the remake is good, what other point is there to be made?

Because Kid in the Front Row always seems to do it first and best (no wonder he doesn't like remakes) he's started a one day blogathon in which bloggers were invited to weigh in with their thoughts on remakes, sequels and reboots. Of course, never wanting to miss the chance to chime in and always happy to have content given to me, here's my take.

It's easy these days to throw Hollywood under the bus and call them creatively bankrupt because it seems that they will remake, reboot and make a sequel to just about anything they can get their hands on. That's the current state of mainstream cinema. We've seen it all summer and it extends out into the peripherals of the entire year as well. However, because this is the current state of cinema, it's what we are left to deal with. We could sit here and argue all day that Hollywood needs to turn it around, find original content, and so on. That is, of course, ideal but to do so is to think about what we want as opposed to deal with what we have. You end up missing a lot of good movies that way.

Personally I am fine with remakes/sequels/reboots. I am fine with it not because I want to see other versions of films I've already seen but because a good film by any other name...as Shakespeare once wrote. If a sequel is well made, than who cares what source it was derived from? And where is it written in stone that al movies based on original content will automatically be good? We spend so much time these days concerned with everything surrounding a movie from it's origins; the tabloid exploits of its players; how much money it made or lost; how good the original was; how this should never have been remade; how stupid Hollywood is, etc., that we almost forget that the film is what is most important: story, characters, acting, direction, editing, lighting, cinematography and how all of these things collide into one another to make magic. That's what's important, everything else is gravy.

And sequels/remakes/reboots, taken as an original concept and not a current fad, also serve a very specific purpose. Godard once said that the best way to criticise a film is to make another. So why not remake a bad movie, or take a different approach, start again from scratch, whatever? The reality of it is that, depending on the circumstances, it will either work or it won't. But that's the same for original films as well. Godard's Breathless was remade in Hollywood and didn't work. You can't take a film that defined a generation with it's originality and invention and make it into a standard Hollywood drama. However, when Sergio Leone used Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo, almost line-for-line, as the inspiration for his Fistfull of Dollars, a whole new genre was born. The difference was that Breathless took the story and simply put it back on film. Leone on the other hand, took Yojimbo and made it his own. That's the success of a remake. That's the success of any film, no matter the source.

And really, what defines an original film? Even original films are rarely ever true originals, and when they are, we sometimes never even hear of them. But just look at some of the past year's original works: Crazy Heart was The Wrestler meets Tender Mercies; Avatar was every classic American western and even Inception was just made up of pieces of every previous Christopher Nolan fil; The Prestige in particular. The definition of an original film is that it wasn't adapted from any existing source, but the idea or true originality usually stops there. History is destined to repeat itself. Hollywood just gets around to it faster than most.

So, do I want to see great films remade? No, but hey, if someone needs to take a little from Hidden Fortress to make a Star Wars, I'm okay with that. And if it takes three decent movies to get to the best Jason Bourne one, I'm okay with that too. Ideally Hollywood would only remake or reboot bad movies with the intention of making them better. But again, we're speaking in ideals and missing the point: if the the remake is good, what other point is there to be made?

Labels:

Akiria Kurosawa,

Breathless,

Hidden Fortress,

Jean-Luc Godard,

Reboots,

Remakes,

Sequels,

Star Wars

Monday, July 26, 2010

Is It Really That Bad?

Writers and critics tend to make, sometimes shameless, use of hyperbole. That's what calling the summer of 2010 the worst summer at the movies ever is. Strangely, I've read, if not exactly that statement, something close to it more often than not. Even many reviews of Inception seem to need to first provide some context by letting readers know that this movie has come out in an awful summer. But what are people basing this on? We need some context for the context. What are you defining as a "bad summer?" Is there another bad summer which we are using for a comparative starting point, or is there a clear definition of what a good summer at the movies needs to look like?

If anything, this summer is no worse than last summer. Actually it may be a little better, and it's not even over yet. Sure, not many of the titles will go down in history, but how many of them actually ever do? The summer is about kicking back, having fun, letting the critical safety net slip a little and just enjoying yourself. Sure, Hollywood is phoning it in this summer but who cares that few of these movies will stand the test of time? The point is, as Pauline Kael once wrote to not consume great art, but to enjoy ourselves.

And enjoy myself I have been. Sure the box office is down on a lot of films and maybe next year Hollywood will have learned their lesson and give us less films edited in blenders on full speed and more big budget entertainments made by competent craftsmen who know how to walk the line between commercial and quality. But on that note, we work with what we have not what we want, and what we have, when you look at the titles, isn't half bad.

Sure there were some big stinkers. Sex and the City 2 is about as bad a movie as I can think of, The A-Team was just about the worst made action movie of the year and Twilight:Eclipse was bad, but who thought it wouldn't be? And even with the latter titles, there were some out there who sincerely enjoyed A-Team and argued that Eclipse was the best of the three movies thus far, whatever that means. Also Marmaduke and Killers crashed and burned and although Shrek 4 raked in the dough, Shrek hasn't been good since the first film. And oh ya, The Last Airbender. 'Nuff said.

And then, there were a lot of good ones. The Losers opened the summer to embarrassing numbers but was still a highly enjoyable action movie with a nice performance from Jason Patrick. Both Get Him to the Greek and The Karate Kid were sequels/remakes with no expectations that delivered on the goods. Iron Man 2 didn't quite work for me but it did for a lot of others and even though I think Toy Story 3 is more minor than many have given it credit for, Pixar still managed to deliver again.

Although some of the more cynical and jaded skipped Knight and Day because it's star once jumped on a couch, it was a genuinely well made, funny action flick and now Salt is supposed to be even better, getting a four star review from Roger Ebert. Even kid flicks Despicable Me and Ramona and Beezus with Selena Gomez are getting surprisingly good reviews. Not to mention the smaller charmers that snuck through the cracks like the wonderful basketball romance Just Wright, Cyrus with Jonah Hill and The Kids Are Alright with Julianne Moore. And, of course, Inception, which was praised by critics, loved by audiences and was certainly the kind of large scale entertainment that every summer needs.

And look, we still have a whole month to go. August, which used to be the month where studios dumped their leftovers has some very promising titles. Will Farrell will maybe redeem his last two or three bad movies against Mark Whalberg in The Other Guys; guilty pleasure series Step-Up will be hitting 3D; Middle Men about the start of Internet porn looks like a teen sex comedy meets Goodfellas; Sylvester Stallone's The Expendables will hopefully bring back the 80s action movie hero aesthetic and give action movies exactly what they've been missing all these years; and Scott Pilgrim doesn't quite have me sold because Edgar Wright still hasn't proven himself to be a great director but many are foaming at the mouth waiting for it.

There's also Eat Pray Love, a human drama with Julia Roberts, a new Nanna McPhee movie, a new Drew Barrymore romantic comedy with the always charming Justin Long, Takers, an interesting looking heist movie and could The Last Exorcism be the new Paranormal Activity? I'm looking forward to finding out.

Writers and critics tend to make, sometimes shameless, use of hyperbole. That's what calling the summer of 2010 the worst summer at the movies ever is. Strangely, I've read, if not exactly that statement, something close to it more often than not. Even many reviews of Inception seem to need to first provide some context by letting readers know that this movie has come out in an awful summer. But what are people basing this on? We need some context for the context. What are you defining as a "bad summer?" Is there another bad summer which we are using for a comparative starting point, or is there a clear definition of what a good summer at the movies needs to look like?

If anything, this summer is no worse than last summer. Actually it may be a little better, and it's not even over yet. Sure, not many of the titles will go down in history, but how many of them actually ever do? The summer is about kicking back, having fun, letting the critical safety net slip a little and just enjoying yourself. Sure, Hollywood is phoning it in this summer but who cares that few of these movies will stand the test of time? The point is, as Pauline Kael once wrote to not consume great art, but to enjoy ourselves.

And enjoy myself I have been. Sure the box office is down on a lot of films and maybe next year Hollywood will have learned their lesson and give us less films edited in blenders on full speed and more big budget entertainments made by competent craftsmen who know how to walk the line between commercial and quality. But on that note, we work with what we have not what we want, and what we have, when you look at the titles, isn't half bad.

Sure there were some big stinkers. Sex and the City 2 is about as bad a movie as I can think of, The A-Team was just about the worst made action movie of the year and Twilight:Eclipse was bad, but who thought it wouldn't be? And even with the latter titles, there were some out there who sincerely enjoyed A-Team and argued that Eclipse was the best of the three movies thus far, whatever that means. Also Marmaduke and Killers crashed and burned and although Shrek 4 raked in the dough, Shrek hasn't been good since the first film. And oh ya, The Last Airbender. 'Nuff said.

And then, there were a lot of good ones. The Losers opened the summer to embarrassing numbers but was still a highly enjoyable action movie with a nice performance from Jason Patrick. Both Get Him to the Greek and The Karate Kid were sequels/remakes with no expectations that delivered on the goods. Iron Man 2 didn't quite work for me but it did for a lot of others and even though I think Toy Story 3 is more minor than many have given it credit for, Pixar still managed to deliver again.

Although some of the more cynical and jaded skipped Knight and Day because it's star once jumped on a couch, it was a genuinely well made, funny action flick and now Salt is supposed to be even better, getting a four star review from Roger Ebert. Even kid flicks Despicable Me and Ramona and Beezus with Selena Gomez are getting surprisingly good reviews. Not to mention the smaller charmers that snuck through the cracks like the wonderful basketball romance Just Wright, Cyrus with Jonah Hill and The Kids Are Alright with Julianne Moore. And, of course, Inception, which was praised by critics, loved by audiences and was certainly the kind of large scale entertainment that every summer needs.

And look, we still have a whole month to go. August, which used to be the month where studios dumped their leftovers has some very promising titles. Will Farrell will maybe redeem his last two or three bad movies against Mark Whalberg in The Other Guys; guilty pleasure series Step-Up will be hitting 3D; Middle Men about the start of Internet porn looks like a teen sex comedy meets Goodfellas; Sylvester Stallone's The Expendables will hopefully bring back the 80s action movie hero aesthetic and give action movies exactly what they've been missing all these years; and Scott Pilgrim doesn't quite have me sold because Edgar Wright still hasn't proven himself to be a great director but many are foaming at the mouth waiting for it.

There's also Eat Pray Love, a human drama with Julia Roberts, a new Nanna McPhee movie, a new Drew Barrymore romantic comedy with the always charming Justin Long, Takers, an interesting looking heist movie and could The Last Exorcism be the new Paranormal Activity? I'm looking forward to finding out.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Why Inception Didn't Save the Movies

Inception is not the savior of all cinema. It's a good movie. It's an even better action movie. But what else is it? Sure, as I stated in my five star review, it's intelligent and complex and we don't get that much in movies anymore, especially summer ones, but it kind of stops there. Maybe if people wouldn't have built it up as something to be compared to the second coming of Christ before they had even seen it than it would have had a deeper impact on me. When I'm looking for action and confronted with psychology, I'm intrigued. When I'm looking for psychology and confronted with action and fractured narrative, I'm entertained. See the difference?

In fact, Inception may be, now upon thinking about it, the most self-reflexive movie I can think of that forecasts its own shortcomings. Like it's hero Cobb it breaks it's own rules and becomes the victim of it's own psychobabble. One of Cobb's musings within the film is that an idea is like a parasite that is impossible to kill. It will simply latch onto the brain and grow until it has consumed the person's entire life. It's funny then that the film itself wouldn't heed its own ponderings. The film is, narratively speaking, ultimately rendered too mechanical because it focuses on an idea that seems to consume the every aspect of its telling.

The idea is that dreams can be entered and manipulated; that they have different layers and levels and such. The film's dialogue concentrates so heavily on talking about dreams and explaining different forms of dream logic, and discussing different waking mental states and philosophies about the nature between dream and reality and how it is possible for one to corrupt and consume the other, that by the time it is over we know everything about dreams but next to nothing about the characters in the film or what they are doing. As Jim Emerson and David Edlestein have rightly criticized, the entire film is more a narrative maze than an involving meditation of the division between dream and reality.

It's ironic then that this hasn't been a problem with past Nolan films. In his two best films The Dark Knight and The Prestige Nolan also created films about ideas and such but the difference was that the ideas were represented by the characters as opposed to the characters being at the service of the idea. Thus, to understand the idea was to understand the character. So when Nolan drew in ponderings on Darwinian order in The Prestige or created the Joker as a Freudian study in the uncanny in The Dark Knight, that was a way in order to help us understand the character while also digging deeper into the overall thematic elements. The Joker was so scary because his ideas about society and chaos and evil were ultimately human and thus we understood the psychology of his character on a ground level and could relate to him as such. But once we understand the nature of dreams in Inception, what are we left with but a bunch of masterful action sequences and a trick ending?

Interesting enough, Jim Emerson wrote yet another of his anti-Inception posts in which he starts the article off with an interesting quote from Stephanie Zacharek that states, "If the career of Christopher Nolan is any indication, we've entered an era in which movies can no longer be great. They can only be awesome, which isn't nearly the same thing."

She's absolutely right, about Inception and Memento anyway. Inception is an awesome technical tour-de-force and that's what I awarded my five stars based on. As an action movie it's about as good as they come. However, as the saviour of cinema, Inception is a false prophet.

Inception is not the savior of all cinema. It's a good movie. It's an even better action movie. But what else is it? Sure, as I stated in my five star review, it's intelligent and complex and we don't get that much in movies anymore, especially summer ones, but it kind of stops there. Maybe if people wouldn't have built it up as something to be compared to the second coming of Christ before they had even seen it than it would have had a deeper impact on me. When I'm looking for action and confronted with psychology, I'm intrigued. When I'm looking for psychology and confronted with action and fractured narrative, I'm entertained. See the difference?

In fact, Inception may be, now upon thinking about it, the most self-reflexive movie I can think of that forecasts its own shortcomings. Like it's hero Cobb it breaks it's own rules and becomes the victim of it's own psychobabble. One of Cobb's musings within the film is that an idea is like a parasite that is impossible to kill. It will simply latch onto the brain and grow until it has consumed the person's entire life. It's funny then that the film itself wouldn't heed its own ponderings. The film is, narratively speaking, ultimately rendered too mechanical because it focuses on an idea that seems to consume the every aspect of its telling.

The idea is that dreams can be entered and manipulated; that they have different layers and levels and such. The film's dialogue concentrates so heavily on talking about dreams and explaining different forms of dream logic, and discussing different waking mental states and philosophies about the nature between dream and reality and how it is possible for one to corrupt and consume the other, that by the time it is over we know everything about dreams but next to nothing about the characters in the film or what they are doing. As Jim Emerson and David Edlestein have rightly criticized, the entire film is more a narrative maze than an involving meditation of the division between dream and reality.

It's ironic then that this hasn't been a problem with past Nolan films. In his two best films The Dark Knight and The Prestige Nolan also created films about ideas and such but the difference was that the ideas were represented by the characters as opposed to the characters being at the service of the idea. Thus, to understand the idea was to understand the character. So when Nolan drew in ponderings on Darwinian order in The Prestige or created the Joker as a Freudian study in the uncanny in The Dark Knight, that was a way in order to help us understand the character while also digging deeper into the overall thematic elements. The Joker was so scary because his ideas about society and chaos and evil were ultimately human and thus we understood the psychology of his character on a ground level and could relate to him as such. But once we understand the nature of dreams in Inception, what are we left with but a bunch of masterful action sequences and a trick ending?

Interesting enough, Jim Emerson wrote yet another of his anti-Inception posts in which he starts the article off with an interesting quote from Stephanie Zacharek that states, "If the career of Christopher Nolan is any indication, we've entered an era in which movies can no longer be great. They can only be awesome, which isn't nearly the same thing."

She's absolutely right, about Inception and Memento anyway. Inception is an awesome technical tour-de-force and that's what I awarded my five stars based on. As an action movie it's about as good as they come. However, as the saviour of cinema, Inception is a false prophet.

Labels:

Christopher Nolan,

Inception,

The Dark Knight,

The Prestige

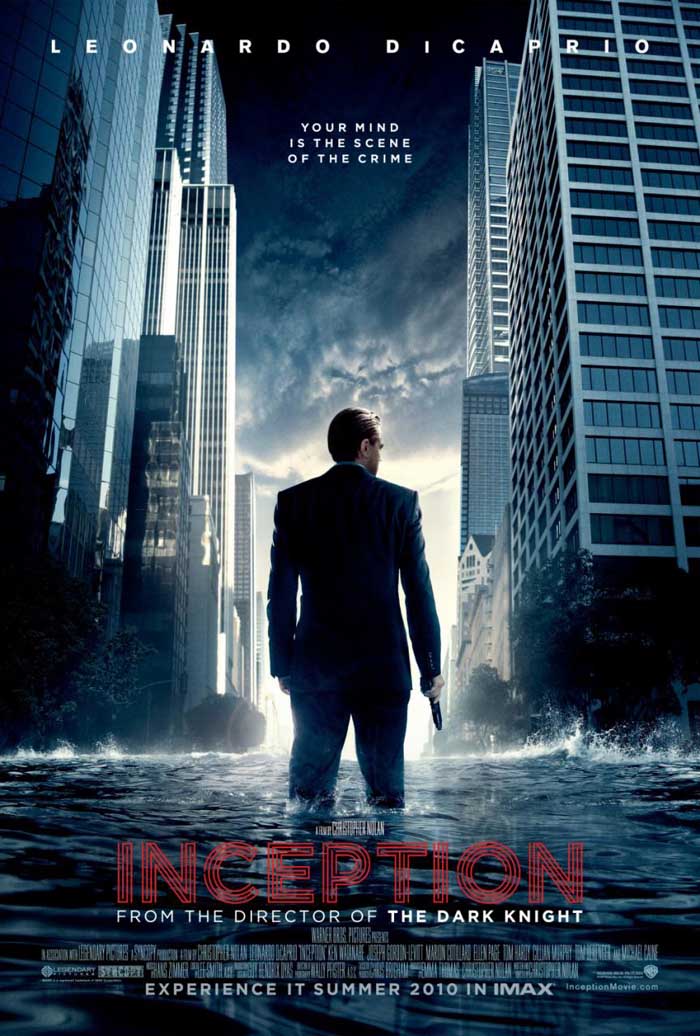

Inception

Inception is best appreciated as an action movie. That is, after all, what it is. Sure it’s so complex that it folds in and upon itself time and again; it chews on endless psychobabble about dreams and unconsciousness and how reality and dream can overlap and be mistaken and replace each other and, on top of all that, it swims with all of director Christopher Nolan’s thematic stand-bys: Freud, Darwin, Jung. But really what it does first and foremost is satisfy Godard’s inkling that you only need two things to make a movie: a girl and a gun. In terms of girls and guns, Inception's just about got ‘em all beat.

Although the plot is complex by definition and trying to explain its every nuance here would be a near impossibility the concept is relatively simple: Inception is almost the exact same movie as Nolan’s The Prestige except, instead of a trick within a trick within a trick it deals with a dream within a dream within a dream. I guess Renoir was right when he said that filmmakers are destined to make the same film over and over again. Think about it: both films are about men driven to extremes by the death of the women they love; both deal in threes; both have characters that exist in worlds where fiction and reality are easily confused; both feature men who are consumed by the unreal; both are about extracting secret information from a nemesis; and both end on the same ambiguous thematic note. This time there’s just more boom boom along the way.

So anyway, here goes: Leonard Dicaprio plays Cobb a man who uses futuristic technology to build dream worlds for his enemies, go into them and steal secret information from them while they don’t know that in reality, they are somewhere dreaming. The dream can, as we are shown in the confounding opening sequence that throws us headlong into the plot, can exist on multiple levels of consciousness in which the dreamer can be taken into another dream.

Cobb used to be a great architect until the death of his wife, which forced him to flee the country. Problem is, she keeps appearing in the dreams because he can’t let her go. It’s possible, you see, for a person in the dream to reflect their own subconscious memories and so therefore Cobb hires Airadne (Ellen Page) to build the dream worlds for him because, if he doesn’t know the layout, it will be harder for Moll (Marian Cotillard) to find them when they are in the process of an excavation and ruin everything.

The newest job is risky because it involves not extraction but inception: going into a persons head and planting an idea, which will grow into a reality and consume their life. This is to help businessman Saito (Ken Wantanabe) take over his competition. The mechanics of the plot can be, from here on in, left up to the viewer to discover.

What’s incredible about Inception is what an assured big budget filmmaker Christopher Nolan has become. Inception is the kind of film every filmmaker dreams of making but only gets the chance to after they’ve broken half a billion at the box office or won an Oscar. It’s a personal, affecting film, filled to the brim with intelligence and interesting ideas. There was once a time when movies were based on original concepts and made by great filmmakers who not only knew how to entertain, but trusted the audience enough not only to be able to follow along but want to. Avatar was such a film last year. Now Inception is another.

However, like all personal films by filmmakers who have found the power to not be pushed around by studios, Inception isn’t perfect. Like Nolan’s monumental The Dark Knight, the story is most interesting after it gets on with setting up context and explaining itself. A lot of the dialogue that relates specifically to dreams sounds more like psychology 101 lectures than actual talk, but once the story gets in motion and feels comfortable rolling forward, it’s nothing short of big budget, edge-of-your-seat excitement that is second to none.

Nolan’s greatest asset as the architect of this story is in his ability to juggle three or four levels of reality at the same time without confusing the plot and does a brilliant job of showing how, when something happens in one dream state, it affects what is going on in another, as is the case with the film's very best sequence in a hallway corridor without gravity. It’s an action sequence for the books. Inception may not be the saviour of all cinema as some predicted it to be but it certainly is the best action movie out there right now. It may even be the best action movie since The Dark Knight. That’s no small feat.

Inception is best appreciated as an action movie. That is, after all, what it is. Sure it’s so complex that it folds in and upon itself time and again; it chews on endless psychobabble about dreams and unconsciousness and how reality and dream can overlap and be mistaken and replace each other and, on top of all that, it swims with all of director Christopher Nolan’s thematic stand-bys: Freud, Darwin, Jung. But really what it does first and foremost is satisfy Godard’s inkling that you only need two things to make a movie: a girl and a gun. In terms of girls and guns, Inception's just about got ‘em all beat.

Although the plot is complex by definition and trying to explain its every nuance here would be a near impossibility the concept is relatively simple: Inception is almost the exact same movie as Nolan’s The Prestige except, instead of a trick within a trick within a trick it deals with a dream within a dream within a dream. I guess Renoir was right when he said that filmmakers are destined to make the same film over and over again. Think about it: both films are about men driven to extremes by the death of the women they love; both deal in threes; both have characters that exist in worlds where fiction and reality are easily confused; both feature men who are consumed by the unreal; both are about extracting secret information from a nemesis; and both end on the same ambiguous thematic note. This time there’s just more boom boom along the way.

So anyway, here goes: Leonard Dicaprio plays Cobb a man who uses futuristic technology to build dream worlds for his enemies, go into them and steal secret information from them while they don’t know that in reality, they are somewhere dreaming. The dream can, as we are shown in the confounding opening sequence that throws us headlong into the plot, can exist on multiple levels of consciousness in which the dreamer can be taken into another dream.

Cobb used to be a great architect until the death of his wife, which forced him to flee the country. Problem is, she keeps appearing in the dreams because he can’t let her go. It’s possible, you see, for a person in the dream to reflect their own subconscious memories and so therefore Cobb hires Airadne (Ellen Page) to build the dream worlds for him because, if he doesn’t know the layout, it will be harder for Moll (Marian Cotillard) to find them when they are in the process of an excavation and ruin everything.

The newest job is risky because it involves not extraction but inception: going into a persons head and planting an idea, which will grow into a reality and consume their life. This is to help businessman Saito (Ken Wantanabe) take over his competition. The mechanics of the plot can be, from here on in, left up to the viewer to discover.

What’s incredible about Inception is what an assured big budget filmmaker Christopher Nolan has become. Inception is the kind of film every filmmaker dreams of making but only gets the chance to after they’ve broken half a billion at the box office or won an Oscar. It’s a personal, affecting film, filled to the brim with intelligence and interesting ideas. There was once a time when movies were based on original concepts and made by great filmmakers who not only knew how to entertain, but trusted the audience enough not only to be able to follow along but want to. Avatar was such a film last year. Now Inception is another.

However, like all personal films by filmmakers who have found the power to not be pushed around by studios, Inception isn’t perfect. Like Nolan’s monumental The Dark Knight, the story is most interesting after it gets on with setting up context and explaining itself. A lot of the dialogue that relates specifically to dreams sounds more like psychology 101 lectures than actual talk, but once the story gets in motion and feels comfortable rolling forward, it’s nothing short of big budget, edge-of-your-seat excitement that is second to none.

Nolan’s greatest asset as the architect of this story is in his ability to juggle three or four levels of reality at the same time without confusing the plot and does a brilliant job of showing how, when something happens in one dream state, it affects what is going on in another, as is the case with the film's very best sequence in a hallway corridor without gravity. It’s an action sequence for the books. Inception may not be the saviour of all cinema as some predicted it to be but it certainly is the best action movie out there right now. It may even be the best action movie since The Dark Knight. That’s no small feat.

Labels:

Christopher Nolan,

Inception,

Leonardo DiCaprio,

The Prestige

Monday, July 19, 2010

One Minutes Review: The Tracey Fragments (2 out of 5)

Bruce McDonald's The Tracey Fragments is not a film, it's a digital media experiment. The problem with experiments though is that sometimes they push so hard and so far that all they end up proving is that they are possible. That's kind of the approach on display here. The film doesn't really have a story other than that the main character Tracey (Ellen Page) is a depressed 16-year old from a dysfunctional family who has been disowned after her younger brother, who thinks he is a dog, has disappeared. We don't get to know much about the characters except what Tracey tells us. "I'm no different than any other normal teenage girl who hates herself," or "You heard the story about the retarded couple who had a kid? That was me." McDonald's approach to this material, which would be typical angsty teen indie melodrama otherwise, is to constantly split the screen up into fragments. At any given moment we are subjected to anywhere from 4 to 12 different images parading across the screen at one time. Sometimes they are adjacent to one another and sometimes within one another; sometimes within the same scene from different angles and sometimes showing us something completely different. The technique allows us to understand Tracey on more of a psychological level than on a traditional story level but it seems as though McDonald isn't using this visual technique for any better reason than to show us that he can. Conversations with Other Women is a great underrated film that used a split screen in order to add another layer of depth and intelligence to a story that would have been otherwise typical melodrama but here, despite some scenes of power and heartbreak, McDonald's hand seems to be ultimately closing on thin air.

Bruce McDonald's The Tracey Fragments is not a film, it's a digital media experiment. The problem with experiments though is that sometimes they push so hard and so far that all they end up proving is that they are possible. That's kind of the approach on display here. The film doesn't really have a story other than that the main character Tracey (Ellen Page) is a depressed 16-year old from a dysfunctional family who has been disowned after her younger brother, who thinks he is a dog, has disappeared. We don't get to know much about the characters except what Tracey tells us. "I'm no different than any other normal teenage girl who hates herself," or "You heard the story about the retarded couple who had a kid? That was me." McDonald's approach to this material, which would be typical angsty teen indie melodrama otherwise, is to constantly split the screen up into fragments. At any given moment we are subjected to anywhere from 4 to 12 different images parading across the screen at one time. Sometimes they are adjacent to one another and sometimes within one another; sometimes within the same scene from different angles and sometimes showing us something completely different. The technique allows us to understand Tracey on more of a psychological level than on a traditional story level but it seems as though McDonald isn't using this visual technique for any better reason than to show us that he can. Conversations with Other Women is a great underrated film that used a split screen in order to add another layer of depth and intelligence to a story that would have been otherwise typical melodrama but here, despite some scenes of power and heartbreak, McDonald's hand seems to be ultimately closing on thin air.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Buying into the Hype: Why It Doesn't Matter if Inception is Any Good

The point of advertising is to try convince the consumer that they want something that they don't necessarily need. Movie advertising is kind of the same way: it's to convince people that a movie is maybe better than it actually is. And truth be told, on some occasions, the movies linked to the ads are about as good as we hope they are.

But look at District 9. Last summer I was travelling through Pennsylvania where we stopped at a McDonald's for lunch and, on the side of my drink cup, was an alien with an X through it and a logo that said No Alien Zone or something like that. I had no idea what District 9 was about at the time (only knew of it by name) but in that moment I translated that clever bit of advertising into expectation of a great movie. After all, a movie advertised this cleverly must be just as clever no? Well District 9 was clever, but not enough to be more than simple summer entertainment. However, by that point it didn't matter if the movie was good or not. The hype machine has spun its wheels and the ads had done their job and people, despite the film's many misgivings, was deemed to be great.

I hate basing my expectations for movies off of ads and trailers and whatever other lines we are fed before the mass public has even gotten a chance to see it. Although I expect Inception to be a great film, I will still go into it this Tuesday with a blank critical slate. I want it to be great, but I'm prepared for it not to be as well. A lot of bloggers are saying it is in fact great. Some of these people I respect and some I don't. One critic who I do respect, David Edelstein, said it wasn't. He didn't like The Dark Knight either. That's fair. Even though I thought the Dark Knight was the best film of the year two years ago, in a sense, I had more respect for Edelstein for turning in a negative review, losing the film its 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, because it showed that he had at least stopped and thought through the movie. He's not a contrarian critic like say Armond White. If David Edelstein says a movie doesn't work he must have (his own) good reasons.

I haven't read the Inception review in question yet because I don't read any in full before I have my own on paper, but here's the point: Edelstein was hung out to dry by both peers and viewers alike for his review of the Dark Knight. He's caught flack again for his Inception review (despite it now only sitting at 83% on RT). But why? Just because everyone says Inception is a great movie, Edelstein is a lousy critic for looking inside himself and not finding reasons to agree? The problem is, as I maybe alluded to before, Inception (along with Tarantino and Scorsese films and many others) are advertised as great films, and people buy into that. I'm not trying to pass judgement on Inception for I have yet to see it or anyone who wrote a good positive review of it, but once people build anticipation, once the hype starts rolling, people stop thinking about the reasons why movies are great and instead just accept that, well, it looks great, everyone says Christopher Nolan is a great director, it must be great, and so on down the line.

Too often we as movie fans let this laziness hang over us because it's easier and quicker than dealing with a movie and all it's parts. We fail to form true opinions and argue them fully and, to another extent, we fail to understand film itself. What if, and you never know, Edelstein is the only right opinion across the board? I'm sure the people who rushed to the battle lines never took that into consideration first?

I'll explain with an example. I took a first year film class which had both Memento and Antionioni's Blow-Up on the syllabus. People left the Blow-Up screening in anger. No one knew what to do with it and thus passed it off as garbage. I didn't like it either, but I wasn't satisfied with my dislike of it; that was too easy, and once I began to deal with it, deconstruct it and build it back up in my mind, it revealed itself as a great film and I understood why it was such. Everyone, of course, loved Memento but, you know what, it's not a great film. It's an entertaining one where a young director is playing with plot gimmicks, but it's not a lot more. Once you break it down you're left with nothing really but a hip, stylish, post-modern film noir that people like because it is "different."

Nolan has, of course, with Batman Begins, proved that he was a great director, solidified it with The Prestige and made sure the title was sticking for good with The Dark Knight. I expect he will continue on in that tradition with Inception but, you never know. The first step is being courageous enough to admit that.

I guess what I'm saying is, what happened to the days before trailers, when people went to films because they wanted to know if they were good or not and they broke film down in order to talk intelligently about it? Did that die with Pulp Fiction when people started liking it just to let everyone know how hip they are? I'd love to read a good review that called Goodfellas one of the worst movies ever made and justified such a bold stance because it would mean, if nothing else, that at least someone took the time to think about a film intelligently and share what they found. That's more admirable, I think, than another person on the heap saying that Goodfellas or anything else is good because, ya know, Scorsese is God, it's different, it's hip, it's got good dialogue, etc. You can get those conversations around any watercooler. Shouldn't we, as critical voices, be using our medium for something of more substance, or is that too much of an inconvenience?

What do you think?

The point of advertising is to try convince the consumer that they want something that they don't necessarily need. Movie advertising is kind of the same way: it's to convince people that a movie is maybe better than it actually is. And truth be told, on some occasions, the movies linked to the ads are about as good as we hope they are.

But look at District 9. Last summer I was travelling through Pennsylvania where we stopped at a McDonald's for lunch and, on the side of my drink cup, was an alien with an X through it and a logo that said No Alien Zone or something like that. I had no idea what District 9 was about at the time (only knew of it by name) but in that moment I translated that clever bit of advertising into expectation of a great movie. After all, a movie advertised this cleverly must be just as clever no? Well District 9 was clever, but not enough to be more than simple summer entertainment. However, by that point it didn't matter if the movie was good or not. The hype machine has spun its wheels and the ads had done their job and people, despite the film's many misgivings, was deemed to be great.

I hate basing my expectations for movies off of ads and trailers and whatever other lines we are fed before the mass public has even gotten a chance to see it. Although I expect Inception to be a great film, I will still go into it this Tuesday with a blank critical slate. I want it to be great, but I'm prepared for it not to be as well. A lot of bloggers are saying it is in fact great. Some of these people I respect and some I don't. One critic who I do respect, David Edelstein, said it wasn't. He didn't like The Dark Knight either. That's fair. Even though I thought the Dark Knight was the best film of the year two years ago, in a sense, I had more respect for Edelstein for turning in a negative review, losing the film its 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, because it showed that he had at least stopped and thought through the movie. He's not a contrarian critic like say Armond White. If David Edelstein says a movie doesn't work he must have (his own) good reasons.

I haven't read the Inception review in question yet because I don't read any in full before I have my own on paper, but here's the point: Edelstein was hung out to dry by both peers and viewers alike for his review of the Dark Knight. He's caught flack again for his Inception review (despite it now only sitting at 83% on RT). But why? Just because everyone says Inception is a great movie, Edelstein is a lousy critic for looking inside himself and not finding reasons to agree? The problem is, as I maybe alluded to before, Inception (along with Tarantino and Scorsese films and many others) are advertised as great films, and people buy into that. I'm not trying to pass judgement on Inception for I have yet to see it or anyone who wrote a good positive review of it, but once people build anticipation, once the hype starts rolling, people stop thinking about the reasons why movies are great and instead just accept that, well, it looks great, everyone says Christopher Nolan is a great director, it must be great, and so on down the line.

Too often we as movie fans let this laziness hang over us because it's easier and quicker than dealing with a movie and all it's parts. We fail to form true opinions and argue them fully and, to another extent, we fail to understand film itself. What if, and you never know, Edelstein is the only right opinion across the board? I'm sure the people who rushed to the battle lines never took that into consideration first?

I'll explain with an example. I took a first year film class which had both Memento and Antionioni's Blow-Up on the syllabus. People left the Blow-Up screening in anger. No one knew what to do with it and thus passed it off as garbage. I didn't like it either, but I wasn't satisfied with my dislike of it; that was too easy, and once I began to deal with it, deconstruct it and build it back up in my mind, it revealed itself as a great film and I understood why it was such. Everyone, of course, loved Memento but, you know what, it's not a great film. It's an entertaining one where a young director is playing with plot gimmicks, but it's not a lot more. Once you break it down you're left with nothing really but a hip, stylish, post-modern film noir that people like because it is "different."

Nolan has, of course, with Batman Begins, proved that he was a great director, solidified it with The Prestige and made sure the title was sticking for good with The Dark Knight. I expect he will continue on in that tradition with Inception but, you never know. The first step is being courageous enough to admit that.

I guess what I'm saying is, what happened to the days before trailers, when people went to films because they wanted to know if they were good or not and they broke film down in order to talk intelligently about it? Did that die with Pulp Fiction when people started liking it just to let everyone know how hip they are? I'd love to read a good review that called Goodfellas one of the worst movies ever made and justified such a bold stance because it would mean, if nothing else, that at least someone took the time to think about a film intelligently and share what they found. That's more admirable, I think, than another person on the heap saying that Goodfellas or anything else is good because, ya know, Scorsese is God, it's different, it's hip, it's got good dialogue, etc. You can get those conversations around any watercooler. Shouldn't we, as critical voices, be using our medium for something of more substance, or is that too much of an inconvenience?

What do you think?

Labels:

Blow-Up,

Christopher Nolan,

Goodfellas,

Inception,

Pulp Fiction,

The Dark Knight

Sunday, July 11, 2010

The Celebrity Connection- Leonardo DiCaprio

Inception opens in less than a week. It's the movie everyone is getting all hot and bothered over this summer. The early reviews have been almost unanimously positive, some even calling it a masterpiece (I think even Kubrick's name came up on Anne Thompson's blog) but I'm still holding my reservations even though my expectations are huge as well. After all, even though Christopher Nolan is now a great director, his non-Batman movies, with the exception of maybe The Prestige, have been more admirable than outright great. There was a lot of talent and promise on display in Following, Memento and Insomnia but it just wasn't quite breaking through to the levels that it did in the Batman movies, especially The Dark Knight. So let's hope that The Dark Knight wasn't a fluke; that it's success was due to people appreciating a good movie and not only wanting to see a fallen star and that Inception does very well. On that note, in order to, if you will, add my two cents to the Inception buzz, check it out:

Is Michael Pitt just Leonardo DiCaprio in disguise? You decide.

Toy Story 3

Pixar Animation Studios spends so much time creating timeless family films it’s no surprise that every couple of years they need to phone one in. That’s not to say that films like A Bug’s Life, Monsters Inc., Cars and now Toy Story 3 are bad, they just don’t possess the sweep and the pull of Pixar’s greatest work. They exist, more often than not, to be light and amusing as opposed to vast, exciting, adventurous, and to pull the imagination to the end of the world and back. They’re still magic little films but they’re not the first ones you grab off the shelf when you need a fix.

Toy Story 3 picks up mere days before Andy, now 17, is moving off to college. The toys, stored in a chest, desperate to be played with one last time devise a failed attempt to lure Andy back into his toy chest for one more go. Mom orders Andy to box up all his stuff to separate what will go with him, what will go to the curb and what will collect dust in the attic. Andy, seeing the cowboy Woody (Tom Hanks) and the gang one last time as he roots through his stuff has one brief moment of Proudstian revelation in which he is transported back through all of the great times he shared with his favourite cowboy. It’s funny, after coming of age, to look back over life and see what objects seem to have created deep physiological connections that can trigger emotional responses at a mere glance.

So Andy throws Woody in the college box and bags up Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen) and co. to go to the attic. However, the bag is mistaken as trash and heads for the curb instead. Knowing that Andy would be devastated to lose his old friends, Woody runs to the rescue but the toys all think they have been junked and, out of equal parts spite and heartbreak head for the back of the van where a box of toys is being donated to the Sunnyside Daycare.

This is great opening stuff. Not only has director Lee Unkrich put us right back into engagement with these beloved characters but he, along with writer Michael Arndt of Little Miss Sunshine fame, seems to really understand the psychology of toys. The movie not only understands the important, unbreakable emotional connections that children form with their favourite toys, who, in a sense, are always there through the most important moments of childhood, but it also understands what the owner means to the toys; how they are dedicated to Andy and will forever be there for him whenever he needs them. All they ask in return is to never be forgotten about. Andy may grow up, but does one ever really grow out of their childhood toys? This is what is so special about Pixar films: No matter their subject they always understand their characters, first and foremost, in relation to their dramatic surroundings.

But then the toys get shipped to Sunnyside, which seems great at first. All the other toys welcome them with open arms and assure them that here there will always be kids that will want to play with them. And when those kids leave, it’s no matter because more just as eager will soon arrive. The daycare is run by the old bear Lotso (Ned Beatty) who ships the new toys to the Caterpillar Room where the young children, all riled up from recess, lay waste to them.

In the meantime, knowing his true intentions, Woody escapes the daycare in an attempt to get back to Andy. Back at Sunnyside it turns out that Lotso was once the favourite toy of his owner until he and his accomplice Big Baby and Chuckles were forgotten about one day on a picnic and quickly replaced. Feeling betrayed by his owner, Lotso became bitter and now rules over the daycare with an iron fist along with Baby, Ken (Michael Keaton) and others.

The long middle section at the daycare is essentially one complete action sequence. The toys are trapped, Buzz is reprogrammed, and Woody returns to rescue them in a sequence that plays more like Escape From Alcatraz than the cute adventures of past films, until it finally ends in a junk yard before the fires of hell in which the heroes become less like toys and more like your standard action hero.

The film ends strong with a final scene so touching and moving that it’s a shame the midsection couldn’t live up to the bookends. The action is entertaining enough but these films have always gotten most of their mileage from showing the toys acting like, well, toys. Even what happens to Lotso is a missed opportunity. What could have been one of the films biggest emotional moments becomes no more than standard movie villain commuperance.

And yet, when the toys are being toys, the film has a magic all its own. It’s neat to see how the toys use their specific capabilities in order to evade Lotso and his goons; and Unkrich, a veteran Pixar man, knows how to get big laughs out of small places. When Ken first appears on the balcony of his dream house he takes the elevator down and it moves, not like a real elevator but like a cheap toy one. It’s details like that that keep Pixar at the top of the heap.

Of course there is always the sentimentality, as is the case with old toys, of picking up with these characters so many years since we last saw them. Tom Hanks, still the most endearing man in Hollywood, is perfect as Woody, the good hearted do gooder; Allen is still doing Buzz as what he is: the best movie part the man has ever had; Joan Cusack is lovely once again as cowgirl Jessie; Michael Keaton is the best choice one could imagine for Ken and no actor other than Beatty as Lotso could play a lovable bear with dark tones lurking just below the surface.

And then the film ends with a classic Pixar moment in which Andy and the toys both find solace in each other one last time before the inevitable must happen. The film opens musically with Randy Newman’s You Got a Friend in Me. It could very well have ended with Tom Waits’ I Don’t Wanna Grow Up.

Pixar Animation Studios spends so much time creating timeless family films it’s no surprise that every couple of years they need to phone one in. That’s not to say that films like A Bug’s Life, Monsters Inc., Cars and now Toy Story 3 are bad, they just don’t possess the sweep and the pull of Pixar’s greatest work. They exist, more often than not, to be light and amusing as opposed to vast, exciting, adventurous, and to pull the imagination to the end of the world and back. They’re still magic little films but they’re not the first ones you grab off the shelf when you need a fix.

Toy Story 3 picks up mere days before Andy, now 17, is moving off to college. The toys, stored in a chest, desperate to be played with one last time devise a failed attempt to lure Andy back into his toy chest for one more go. Mom orders Andy to box up all his stuff to separate what will go with him, what will go to the curb and what will collect dust in the attic. Andy, seeing the cowboy Woody (Tom Hanks) and the gang one last time as he roots through his stuff has one brief moment of Proudstian revelation in which he is transported back through all of the great times he shared with his favourite cowboy. It’s funny, after coming of age, to look back over life and see what objects seem to have created deep physiological connections that can trigger emotional responses at a mere glance.

So Andy throws Woody in the college box and bags up Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen) and co. to go to the attic. However, the bag is mistaken as trash and heads for the curb instead. Knowing that Andy would be devastated to lose his old friends, Woody runs to the rescue but the toys all think they have been junked and, out of equal parts spite and heartbreak head for the back of the van where a box of toys is being donated to the Sunnyside Daycare.

This is great opening stuff. Not only has director Lee Unkrich put us right back into engagement with these beloved characters but he, along with writer Michael Arndt of Little Miss Sunshine fame, seems to really understand the psychology of toys. The movie not only understands the important, unbreakable emotional connections that children form with their favourite toys, who, in a sense, are always there through the most important moments of childhood, but it also understands what the owner means to the toys; how they are dedicated to Andy and will forever be there for him whenever he needs them. All they ask in return is to never be forgotten about. Andy may grow up, but does one ever really grow out of their childhood toys? This is what is so special about Pixar films: No matter their subject they always understand their characters, first and foremost, in relation to their dramatic surroundings.

But then the toys get shipped to Sunnyside, which seems great at first. All the other toys welcome them with open arms and assure them that here there will always be kids that will want to play with them. And when those kids leave, it’s no matter because more just as eager will soon arrive. The daycare is run by the old bear Lotso (Ned Beatty) who ships the new toys to the Caterpillar Room where the young children, all riled up from recess, lay waste to them.

In the meantime, knowing his true intentions, Woody escapes the daycare in an attempt to get back to Andy. Back at Sunnyside it turns out that Lotso was once the favourite toy of his owner until he and his accomplice Big Baby and Chuckles were forgotten about one day on a picnic and quickly replaced. Feeling betrayed by his owner, Lotso became bitter and now rules over the daycare with an iron fist along with Baby, Ken (Michael Keaton) and others.

The long middle section at the daycare is essentially one complete action sequence. The toys are trapped, Buzz is reprogrammed, and Woody returns to rescue them in a sequence that plays more like Escape From Alcatraz than the cute adventures of past films, until it finally ends in a junk yard before the fires of hell in which the heroes become less like toys and more like your standard action hero.

The film ends strong with a final scene so touching and moving that it’s a shame the midsection couldn’t live up to the bookends. The action is entertaining enough but these films have always gotten most of their mileage from showing the toys acting like, well, toys. Even what happens to Lotso is a missed opportunity. What could have been one of the films biggest emotional moments becomes no more than standard movie villain commuperance.

And yet, when the toys are being toys, the film has a magic all its own. It’s neat to see how the toys use their specific capabilities in order to evade Lotso and his goons; and Unkrich, a veteran Pixar man, knows how to get big laughs out of small places. When Ken first appears on the balcony of his dream house he takes the elevator down and it moves, not like a real elevator but like a cheap toy one. It’s details like that that keep Pixar at the top of the heap.

Of course there is always the sentimentality, as is the case with old toys, of picking up with these characters so many years since we last saw them. Tom Hanks, still the most endearing man in Hollywood, is perfect as Woody, the good hearted do gooder; Allen is still doing Buzz as what he is: the best movie part the man has ever had; Joan Cusack is lovely once again as cowgirl Jessie; Michael Keaton is the best choice one could imagine for Ken and no actor other than Beatty as Lotso could play a lovable bear with dark tones lurking just below the surface.

And then the film ends with a classic Pixar moment in which Andy and the toys both find solace in each other one last time before the inevitable must happen. The film opens musically with Randy Newman’s You Got a Friend in Me. It could very well have ended with Tom Waits’ I Don’t Wanna Grow Up.

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Celebrities Behaving Badly

So apparently Mel Gibson is taking career advice from Sean Penn and Christian Bale. We've read the stories about how he said racist things and verbally abused his ex squeeze Oksana Grigorieva but now we finally have the audio. It's strange that a man who rose to stardom because of his natural likability and boyish charm could be so cold and oppressive to this woman. On the plus side, I really like at the end when he says she can stay in the house. He's not giving it to her, but she can stay. At least he's being the bigger man in the situation.

So apparently Mel Gibson is taking career advice from Sean Penn and Christian Bale. We've read the stories about how he said racist things and verbally abused his ex squeeze Oksana Grigorieva but now we finally have the audio. It's strange that a man who rose to stardom because of his natural likability and boyish charm could be so cold and oppressive to this woman. On the plus side, I really like at the end when he says she can stay in the house. He's not giving it to her, but she can stay. At least he's being the bigger man in the situation.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Am I Missing Something?

Here's a funny question for someone who is more well versed on the subject than I. I was reading Roger Ebert's review for Twilight:Eclipse and he made a comment about the tent scene between Edward and Jacob. It was in jest, but Ebert made reference to Brokeback Mountain.

Then I was looking at IMDB to see who would be directing the fourth film and saw that it was Bill Condon, an openly gay man. I then saw in the trivia section that at one point Gus Van Sant, another openly gay man, had been in talks to also direct the fourth film. Considering that both of these men's films, if not dealing with gay characters, have homosexual undercurrents running through them, is there something inherently homosexual about Breaking Dawn or Twilight as a whole? Is it in the books? I think there could be an interesting reading here, but I don't think I'm expert enough on the Twilight universe to give it.

Any thoughts?

Here's a funny question for someone who is more well versed on the subject than I. I was reading Roger Ebert's review for Twilight:Eclipse and he made a comment about the tent scene between Edward and Jacob. It was in jest, but Ebert made reference to Brokeback Mountain.

Then I was looking at IMDB to see who would be directing the fourth film and saw that it was Bill Condon, an openly gay man. I then saw in the trivia section that at one point Gus Van Sant, another openly gay man, had been in talks to also direct the fourth film. Considering that both of these men's films, if not dealing with gay characters, have homosexual undercurrents running through them, is there something inherently homosexual about Breaking Dawn or Twilight as a whole? Is it in the books? I think there could be an interesting reading here, but I don't think I'm expert enough on the Twilight universe to give it.

Any thoughts?

Labels:

Bill Condon,

Breaking Dawn,

Gus Van Sant,

Twilight,

Twilight:Eclipse

The Celebirty Connection-Six Feet Under

I don't really watch TV but in grade 12 I discovered Six Feet Under and was hooked. I watched every episode of the first season. Too bad that by the time Season 2 came to Canada on a channel that didn't require a subscription I was living in a TV-less university dorm. Over the years I have picked up all five seasons on DVD but have only started rewatching them now. I just got through the entirety of the first season again and will be moving on to the second soon. However, I noticed something about the artwork:

Monday, July 5, 2010

Filmic Measures-The Documentary Rule

When Gene Siskel said that a movie needed to be better than having lunch with its stars he, in a way, unconsciously, if not changed film criticism, than changed the way films are consumed. Although the statement was, I assume, meant merely as a means to have a quotable critical tagline for which to evaluate movies, the buried implications are worth unearthing. To think about films this way is to uncover their relationship to the world or art, society, etc, for a film, in order to succeed, must always be better than something else. Is there another art that bears such a burden? Theatre is comparable to other theatre, music is judged based on it's worth next to other music and the success of the writer depends on their ability to convey meaningful thoughts through words.

But film is at once art, culture, politics, philosophy, psychology anthropology, history, sociology, what have you on top of all the physical tradesmen it employs simple to make it happen. And although all art is, in some way, influenced by these things, does any but film ever truly embody them? Most arts, after all, usually have something that keeps art separated, for lack of better phrasing, from politics. The play has the luxury of unfolding in real time in front of a crowd in which, if one desired, could be reached out and touched, but it is, aesthetically speaking, built upon the suspension of disbelief. The writer is not so much responsible for the events they depict as they are their interpretation of such, which are only as real as the writer's negotiation of them. The writer has poetry on their side. But, because of this disconnection, to come full circle, theater must only be better than other theatre, the novel only better than other novels, etc.

But film, despite the "lie" of editing as Godard would have it, is captured with sound, movement, colour. It's a literal embodiment of whatever has been placed before the camera, no matter how artificial it's construction may have been. Film must not only be art, politics, philosophy, etc., it must be better than art, politics, philosophy, etc.

That's why we're always judging film based not only on reality, believability, aesthetic invention and so on, but also the depth of it's thoughts, it's moral centre, it's ability to speak something, anything, be it the banal or the humorous. To paraphrase what Ossie Davis once said: art is a form of power; it has the ability to move us and make us move. Is there, looking back on history, a more powerful art form, in this sense, than film?

That's why we create these sayings, these filmic measures because, as Siskel pointed to us, all film must be better than something else. So here's one: A film must be better than a documentary made on the same subject. The difference between fiction and documentary is simple: documentary is fact, fiction is being there (note-I am using fact in an abstract way, not in a literal way as if to suggest that documentaries are not subjective). A fiction film should take you to the heart of it's subject, take you along for its journey, let you understand its hero and their cause, morals, beliefs, whatever it is that makes the experience as personal and intimate as possible. A documentary on the other hand should be, as it's name suggests, a document of something; a chronicling of a belief, a movement, a moment in time. Fiction is built from emotions. Documentary is, in one way or another, built from thesis.