There’s a way some great actors just have of looking off into the distance that really becomes less about performance and more about finding true emotions. It’s a look without dialogue or anything more than a twist of the side of the mouth or a certain glint in the eye that hits something home, be it a man hugging his children or staring off as someone or something leaves him standing behind. It’s also a look that is most startling when comedic actors find it because it’s the moment that they feel comfortable enough with themselves to let the act down and bare some sort of true emotion. Steve Martin does it maybe better than anyone. Now Steve Carrel does it too, first with Dan in Real Life and now, in Crazy, Stupid, Love, he does it again.

It’s a look, especially now in 2011, that makes your realize that movies have become so big, dumb, artificial and ultimately meaningless, that it’s a small treasure to find on that exists at ground level and touches an audience because it deals with people and their actions instead of caricature and plot gimmicks. It’s a look, however that also, unfortunately, makes one wish it had found its way into a better movie.

And thus we have Crazy, Stupid, Love, which, despite its title, which promises insights into the strange, nonsensical, sloppy and completely unpredictable nature of love in real life, can’t muster up much more than to be a run of the mill romantic comedy. It tries too hard to be funny, not hard enough to be insightful, not much to be tightly structured and not at all to be anything more insightful than any other bi-weekly Hollywood romance. It’s good, but not good enough.

Thankfully it finds great actors to raise it into something enjoyable. Steve Carrel is warm, funny and human as Cal, long married to Emily (Julianne Moore). His blazer is too big, he wears running shoes with it, his wallet is Velcro and he’s more or less coasting through the routine his life has become. When Emily tells him she has had an affair with a colleague (Kevin Bacon who's name gets the film’s biggest laugh) and wants a divorce he doesn’t want to talk about it and instead, jumps out of the car to avoid her rambling. At least the pavement feels real.

Then one drunken night at the local haunt he comes across Jacob (Ryan Gosling) a smooth operator with the right suite, the right hair, the right shades, the right accent and the right lines. As, night after night, Jacob watches poor Cal make a drunken fool of himself at the bar he calls him over, tells him he reminds him of someone and says he will teach him everything he knows so he can get his life back together and pick up women so that he can get over Emily, his first and only love.

But then as Cal, after much funny teaching, starts to bag any woman he wants, Jacob meets Hannah (the lovely Emma Stone) who he fails to pick up but comes to him after one night realizing her relationship with her moron boyfriend is going nowhere fast. Hannah, for Jacob, is a game changer and slowly the two stories go their separate directions as Cal and Emily begin to realize their mistakes and Jacob begins to give up his ways.

All of this is nice and funny and sweet and utterly forgettable. If it wasn’t for the presence of Carrel, Stone, Moore and Gosling, the movie would be a redundant mess as it spins it’s wheels to an overblown and predictable conclusion.

But alas, in spite of unfortunate subplots in which Carrel dates a crazy grade school teacher played by Marissa Tomei and another strange and awkward one involving Cal’s family babysitter, the film is charming because it’s stars bring it warmth and humour. Carrel especially, under appreciated because he’s pigeonholed into playing morons, has a way of casting, as indicated in the opening paragraph, human glances across a screen that can either melt or lift your heart and Gosling, so very good in so many kinds of roles, finds a note for Jacob that is more about personality than caricature.

And that’s what the film offers: the pleasure of seeing the right actors come together and breathe life into an otherwise forgettable work. Crazy, Stupid, Love isn’t wholly realistic, doesn’t have any big moments of revelation like the best romantic comedies do and is more concerned with being clever and witty than about creating a full story that is engaging from beginning to end. These are intelligent and attractive actors. They know how to project humour and emotional depth in natural ways. Now that we’ve seen how good they can be in a film on autopilot let’s pray they find another one soon that is worthy of their talents.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Friday, August 19, 2011

Justifying OUr Shitty Taste

So, last week I threw out a call to bloggers to "justify their shitty taste." It was really just something I myself wanted to do but thought I'd open it up to others to see if anyone else wanted to contribute on the topic. Two men stepped up to the plate. Thankfully quality is better than quantity and it was two of the best out there.

So, besides my piece on Knowing, be sure to also check out what Vancetastic had to say about Father's Day over at The Audient and what Yojimbo had to say about Crash over at Let's Not Talk About Movies.

So, besides my piece on Knowing, be sure to also check out what Vancetastic had to say about Father's Day over at The Audient and what Yojimbo had to say about Crash over at Let's Not Talk About Movies.

Labels:

Crash,

Father's Day,

Justify your shitty taste,

Knowing

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

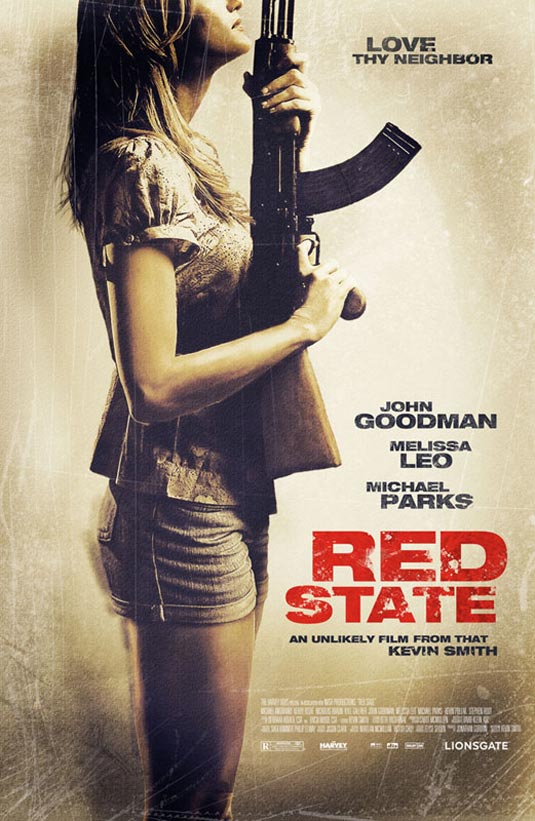

Red State

Kevin Smith’s new religious thriller Red State suffers from “The Problem of the Bicycle.” For those of you who don’t know, the “Problem of the Bicycle” was Michelangelo Antonioni’s criticism put forward towards The Bicycle Thief and Italian neo-realism as a whole. He basically said that, now that we have a movie about a man stealing a bicycle, we need one which understands the man, his psychology, what makes him tick and what ultimately leads him to the point of theft. Meaningful movies, in other words, needed to be about more than action in the present.

That’s what Red State is: all action and no thought. It's cheap slight-of-hand masked as serious social commentary. Here Smith, breaking away from his typical comedy background, is trying to make a serious movie about serious subject matter. Stylistically it works just fine as unnerving, bargain basement grindhouse. Intellectually, the movie is a puff of smoke as our hands close on nothing but thin air.

The story focuses on a mad small town preacher named Abin Cooper (Michael Park in a riveting villain role) who is supposed to represent a Fred Phelps surrogate as him and his small family congregation picket outside the funeral of a locally murdered gay teen, waving signs that say the kid is on his way to hell and other such things. Cooper’s presence is so strong around town that a local high school teacher tells her class that not even the neo-Nazi’s want anything to do with him. This is the extent of characterization in Red State.

Then one night three kids sneak off to lose their virginity to a local girl they found online. This is Sara (Melissa Leo) who says no one it getting into her without getting at least two beers into them. The kids drink down and hit the floor. When they awaken they find themselves inside Cooper’s church as he preaches a sermon of hate and then watches as a gay man, bound in plastic wrap and tied to a cross, is murdered in cold blood.

An investigation ultimately brings around the ATF lead by Keenan (John Goodman), who’s orders are to kill everyone inside after a Davadian-like firefight breaks out. This is the extent of social commentary in Red State; that, oh gosh, maybe even the good guys aren't good guys in the end.

In the Q&A with Smith that followed the screening of Red State he indicated that his purpose for making the movie was to take a stance against organizations like Fred Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church who commit acts of hate in the name of God. This subject matter is exactly the problem as it's too large for a film of such small ambitions. That Smith has no agenda other than to cut down people like Phelps, he see the church people as no more than villains. What Smith fails to realize is that great drama is created in the grey areas that exist between ingrained social concepts of good and evil and how, as humans, people have the freedom to cross those lines at their own free will. It's not enough to show that someone drank the Koolaide when what's most interesting is understanding what forces would lead someone to such an act. The problem of the bicycle.

Instead, Smith has made what he himself deems a “parlour trick” of a movie in which twists are taken and bodies begin to drop, not so much in order to make any sort of statement, but rather for the director to toy with the audience. He’s proven now he can make a movie in another genre and make it well but Red State too often plays too much like the same kid just in a different candy store.

And then the movie ends, not to give anything away, on several notes that I suppose Smith would like to think of as satire but which take a misguided b-movie and turn it into an ignorant one. These scenes reveal the true nature of Smith and his black and white playground politics and lead to a final line of dialogue which corrupts the movie, making Smith just as guilty as those he takes up arms against within the film. If Red State ultimately makes any statement at all it’s that not only am I right and they are wrong but let’s make fun of them for how wrong they are. That Smith can’t find a way to end his film in anything but his standard penis jokes and stoner references reflects the sad state of a boyish mentality trying to juggle with an adult concept.

Smith states that, before wrapping up his career as a filmmaker he wanted to make the kind of film that his contemporaries like Quentin Tarantino and the Cohen Bros make but that he felt he never had the kind of talent as a visual storyteller to pull-off. It’s a funny reference seeing as the Cohen Bros. masterpiece No Country for Old Man is a haunting tale of an evil force that is corrupting society, which is both masterful on a suspense level as well as sending out a haunting warning call about the society we life in. That’s what, I think, Red State ultimately aims for, but Smith never even tries to deal with the idea of evil within society or take account for the ideas he wishes to explore. He's too busy making cheap entertainment for that.

There’s no doubt that Kevin Smith is a talented guy. In the comedy realm he has made some singular films which define their generation and has a voice for dialogue that, like David Mamet, Tarantino or Neil Labute is instantly recognizable as his own. But within the realm of drama and suspense Smith is lost in a sea of his own shortcomings, never being able to decide if he’s making a statement or making the kind of entertainment that gets an audience hooting and hollering. He used to make smart movies for dumb people. Now he has, unfortunately, made nothing more than a dumb movie for smart people.

That’s what Red State is: all action and no thought. It's cheap slight-of-hand masked as serious social commentary. Here Smith, breaking away from his typical comedy background, is trying to make a serious movie about serious subject matter. Stylistically it works just fine as unnerving, bargain basement grindhouse. Intellectually, the movie is a puff of smoke as our hands close on nothing but thin air.

The story focuses on a mad small town preacher named Abin Cooper (Michael Park in a riveting villain role) who is supposed to represent a Fred Phelps surrogate as him and his small family congregation picket outside the funeral of a locally murdered gay teen, waving signs that say the kid is on his way to hell and other such things. Cooper’s presence is so strong around town that a local high school teacher tells her class that not even the neo-Nazi’s want anything to do with him. This is the extent of characterization in Red State.

Then one night three kids sneak off to lose their virginity to a local girl they found online. This is Sara (Melissa Leo) who says no one it getting into her without getting at least two beers into them. The kids drink down and hit the floor. When they awaken they find themselves inside Cooper’s church as he preaches a sermon of hate and then watches as a gay man, bound in plastic wrap and tied to a cross, is murdered in cold blood.

An investigation ultimately brings around the ATF lead by Keenan (John Goodman), who’s orders are to kill everyone inside after a Davadian-like firefight breaks out. This is the extent of social commentary in Red State; that, oh gosh, maybe even the good guys aren't good guys in the end.

In the Q&A with Smith that followed the screening of Red State he indicated that his purpose for making the movie was to take a stance against organizations like Fred Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church who commit acts of hate in the name of God. This subject matter is exactly the problem as it's too large for a film of such small ambitions. That Smith has no agenda other than to cut down people like Phelps, he see the church people as no more than villains. What Smith fails to realize is that great drama is created in the grey areas that exist between ingrained social concepts of good and evil and how, as humans, people have the freedom to cross those lines at their own free will. It's not enough to show that someone drank the Koolaide when what's most interesting is understanding what forces would lead someone to such an act. The problem of the bicycle.

Instead, Smith has made what he himself deems a “parlour trick” of a movie in which twists are taken and bodies begin to drop, not so much in order to make any sort of statement, but rather for the director to toy with the audience. He’s proven now he can make a movie in another genre and make it well but Red State too often plays too much like the same kid just in a different candy store.

And then the movie ends, not to give anything away, on several notes that I suppose Smith would like to think of as satire but which take a misguided b-movie and turn it into an ignorant one. These scenes reveal the true nature of Smith and his black and white playground politics and lead to a final line of dialogue which corrupts the movie, making Smith just as guilty as those he takes up arms against within the film. If Red State ultimately makes any statement at all it’s that not only am I right and they are wrong but let’s make fun of them for how wrong they are. That Smith can’t find a way to end his film in anything but his standard penis jokes and stoner references reflects the sad state of a boyish mentality trying to juggle with an adult concept.

Smith states that, before wrapping up his career as a filmmaker he wanted to make the kind of film that his contemporaries like Quentin Tarantino and the Cohen Bros make but that he felt he never had the kind of talent as a visual storyteller to pull-off. It’s a funny reference seeing as the Cohen Bros. masterpiece No Country for Old Man is a haunting tale of an evil force that is corrupting society, which is both masterful on a suspense level as well as sending out a haunting warning call about the society we life in. That’s what, I think, Red State ultimately aims for, but Smith never even tries to deal with the idea of evil within society or take account for the ideas he wishes to explore. He's too busy making cheap entertainment for that.

There’s no doubt that Kevin Smith is a talented guy. In the comedy realm he has made some singular films which define their generation and has a voice for dialogue that, like David Mamet, Tarantino or Neil Labute is instantly recognizable as his own. But within the realm of drama and suspense Smith is lost in a sea of his own shortcomings, never being able to decide if he’s making a statement or making the kind of entertainment that gets an audience hooting and hollering. He used to make smart movies for dumb people. Now he has, unfortunately, made nothing more than a dumb movie for smart people.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

The Road to Fellini's Realism

Note: For anyone who has followed this blog from the beginning or even just glaced at my profile picture, will know that La Dolce Vita is my favourite movie and Federico Fellini my favourite filmmaker. Over the summer the TIFF Bell Lightbox has been hosting a retrospective of Fellini's work as well as presenting a gallery of images dedicated to him. This coming Sunday I will be seeing Nights of Cabiria on the big screen as well as La Dolce Vita come the end of August. I'm sure I'll have something to say about both when the time comes but until then I publish this essay in anticipation.

The road is a metaphor that could very well describe the entire career of Federico Fellini, whose films, in one way or another, all revolved around a journey of self discovery. So it is ironic that his film, in which respected film critic Roger Ebert called the first “that can be called entirely "Felliniesque"(1994), would be called The Road. In a way it’s a starting point from which Fellini himself would take a journey of self-discovery, establishing the very images, motifs and themes that all of his later work would revolve around. Some of which would be the tone that Fellini’s films created by a rejection of the typical characters found in the neo-realism genre which Fellini was born from as discussed by Peter Bondanella in his book The Films of Federico Fellini. There is also the constant contrast between the circus and religion as discussed by Edward Murray in his book Fellini the Arstist, and finally the constant quest of self discovery that Fellini’s characters take in which they often find themselves trapped somewhere between heaven and earth as discussed by Donald P. Costello in his book Fellini’s Road.

In his book The Films of Federico Fellini, Peter Bondanella talks of Fellini’s departure from his roots as a maker of Italian Neorealist films. Having started in this genre as a writer for Roberto Rossili, Fellini soon abandoned his roots on his third film La Strada, by presenting characters and a plot that surpassed what was found within the neorealist genre. According to Bondanella, “Perhaps his departure from neorealist practice in rejecting the idea of film character as social type is the most important divergence from neorealist practice; but equally important is the fact that the plot and visuals of La Strada reject easy classification as a realistic story of social exploitation” (51-51). If neorealism was thought to have moved cinema away from the Hollywood “dream factory” (43) and into the streets of war torn Europe (43), then Fellini was taking it back into a dream world. According to Bondanella, “Fellini agreed with both Rossellini and Antonioni that Italian cinema needed to pass beyond a dogmatic, Marxist approach to social reality, dealing poetically with other equally compelling personal or emotional problems”(53). Hence, La Strada was born. More so then any of Fellini’s previous films, it was a parable about childlike innocence; about finding the purpose that God put you on earth to fulfill. La Strada therefore gave birth to an even newer realism; Fellini’s realism.

It was easy to see that Fellini’s films, particularly his characters, did not so much offer depictions of realism. Instead they acted as a part within Fellini’s fables. In neorealism it was believed that films should “stress social context” (Bondanella, 43). Fellini rejected this idea; his films were more like a process of working out their maker’s own spiritual life journey through the use of allegory and fable. As Bondanella writes, “More than a story, La Strada is a fable about symbolic figures, and its plot structures this origin in the fable or fairy tale” (52). The way Fellini’s films are structured, La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, and La Dolce Vita in particular, is that they both begin and end at the sea; they come full circle back to their beginnings. For Fellini, especially as a Roman Catholic, this book ending represented a new beginning for his characters, a chance for spiritual redemption. Bondanella offers this explanation: “Rather than viewing the world from the perspective of class struggle or class conflict, La Strada embodies a profoundly Christian emphasis upon the individual and the loneliness of the human condition” (54). In using the image of the sea, Fellini is showing the viewers that his films are not about the underpinnings of a Marxist society, but rather the choices of an individual journey; the journey away from the birthplace and back, in an attempt to find, not a place within society, but a place within the spiritual universe. In Fellini’s reality, faith takes precedence over class.

Besides the road, there are two other images that constantly appear throughout Fellini’s body of work, usually appearing in conflict with one another. One of these images is that of the circus: a place of spontaneity and life, a place where it is the norm to think the unthinkable, to believe the unimaginable. To Fellini, the circus was a place of great imagination and invention. Edward Murray in his book Fellini the Artist states that “Where the circus…appears directly in his pictures, it stands as a metaphor, a device for revealing life as a funny- sad experience with cosmic significance” (232). Indeed, to Fellini, a man who liked to create his own reality, whether it was derived from his own life, or a life he had made up, the circus was a place of unending imagination.

The circus however was not the only part of Fellini’s realism. Fellini was a director who was constantly trying to work out the dual nature of reality, trying to blur the lines between the “real and the ideal” (Murray,234). Thus Fellini’s films present a reality that was not the same one that the neorealists dealt with. Rather it was one that was Fellini’s itself, a world in which imagination and performance were held in the highest regard, and thus the circus was always in constant conflict with the church. In reality, the church reined supreme in Rome, and this is why it was under constant comparison to the circus. As Murray helps us understand, Fellini was constantly trying to show us life’s poles, that every road has two paths, more importantly, “life as it is, and life as it ought to be” (234). Throughout his films Fellini constantly presents the audiences with two versions of life. The life that we have, which is one of banality, hurt and sorrow, and most importantly of displacement, and the life that we could have if we lived a little better, were a little more loving, and lived with a little more direction; a true dolce vita.

For Fellini the circus offered direction where the church did not. The church to Fellini “(S)tands for an inauthentic way of life, since it tends to thwart man’s expansive capacities” (Murray,30). The reality of the church was that it presented a strict way of life, a doctrine that was to be accepted and lived by. To Fellini the church undermined an individual’s imagination. The church was not concerned with poles. In Fellini’s eyes, the church only saw one way to live; their way, which Murray helps to illustrate in pointing out that “(H)is attitude towards the Church is a rebellious one” (31). Murray goes on to state that this is because “(T)he polarities that distinguish the Fellinian universe guarantee the director a sufficiently rich assortment of themes with which to capture the interest of the intelligent viewer, who invariably likes to be shown the different sides of every experience”(31). Alas, the church and the circus need each other. If the church only shows us one side of what life should be, Fellini needed the circus to show us the other.

Although Gesulmina in La Strada never comes into such direct conflict with the church as Fellini’s later characters such as Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1957) or Marcello (La Dolce Vita, 1960) would, we are still able to get a glimpse of how the circus functioned in Fellini’s realism. The poles in this film revolve around the circus and the world outside which in a way, mimics the reality of neorealism; life in a working class society. We see that Gesilmina is unhappy to hear of her sister’s passing and that she will have to take her place alongside Zampano and his traveling circus-like act. Yet it is when she is performing that reality slips away and for a brief moment, she is happy. The circus is able to strip reality away and offer hope when all seems hopeless. That’s the brilliance of Fellini’s realism, when life seemed to be going bad, there were fantasy places like the circus, or on a larger, more metaphorical scale, Fellini’s films themselves, to escape to in order to find comfort and happiness.

Coming back to the metaphor of the road, in his book Fellini’s Road, Donald P. Costello states that “Throughout all his films, Fellini is concerned with the road of life” (5). There is no doubt that one of the main themes throughout all of Fellini’s films is that of a spiritual journey, of a character who is caught between Heaven and Earth, who must journey down this road in order to find their placement in life. To reinforce this idea, Costello states: “Both thematically and formally, a Fellini film is a journey toward discovery of the essential self” (5). In the director’s own words: “(E)ach time I am telling the story of characters in quest of themselves, in search of a more authentic source of life, of conduct, of behavior, that will more closely relate to the true roots of their individually” (Fellini in Costello, 2). This journey usually must be taken, as Fellini’s characters often find themselves trapped between the earth and the sky. In La Strada, The Fool represents the sky and Zampano the Earth. Similarly 8 ½ finds it’s main character Guido being held to earth only by a rope around his foot, and in La Dolce Vita, Marcello is caught between a flying statue of Jesus and a monster from the sea.

In a similar sense, Costello breaks down the three characters of La Strada into a trinity which involves The Child of the Sea (Geselmina), the Spirit of the Sky (The Fool) and the Man of Earth (Zampano) ( 23, 18 and 27 respectively). These three elements, in one form or another, come to represent the spiritual journey that Geselmina, Cabiria, Marcello, Guido, etc, will all have to take along their road to spiritual fulfillment. It is important to note that each of these journeys end with their character’s finding their way back to be offered the possibility of redemption at their place of origin: the sea. For Fellini the sea represented several things. It represented the innocence of youth, the feminine and most importantly, the beginning of life (Costello, 6). It is at the sea in La Strada where Geselmina, although dead, can complete the purpose of her spiritual journey, which was to help Zampano to understand his loss and find redemption on the beach. In a way, although tragic on the surface, the final scene in which Zampano cries on the beach is a baptism for this man, a rebirth which offers a way to start over on a new path of life. This is ultimately the possibility that Fellini presents all of his characters with at the end of his films, some of whom accept it (Cabiria) and some who don’t (Marcello).

Fellini’s films constantly presented a spiritual journey down the road of life. Through three specific texts based on the director’s work, we can see that this journey stood in constant contrast with the Italian Neorealism movement, which presented characters trying to find their place within a Marxist society. We also see that Fellini was constantly contrasting the church with the circus to show us how he viewed the importance of life and imagination. His films also constantly showed the struggle of a character who was stuck somewhere between Heaven and Earth. Through all of these themes and ideas, Fellini was able to create a realism that was not the one that was shared by his audience but one that existed all to himself: a Fellini realism.

The road is a metaphor that could very well describe the entire career of Federico Fellini, whose films, in one way or another, all revolved around a journey of self discovery. So it is ironic that his film, in which respected film critic Roger Ebert called the first “that can be called entirely "Felliniesque"(1994), would be called The Road. In a way it’s a starting point from which Fellini himself would take a journey of self-discovery, establishing the very images, motifs and themes that all of his later work would revolve around. Some of which would be the tone that Fellini’s films created by a rejection of the typical characters found in the neo-realism genre which Fellini was born from as discussed by Peter Bondanella in his book The Films of Federico Fellini. There is also the constant contrast between the circus and religion as discussed by Edward Murray in his book Fellini the Arstist, and finally the constant quest of self discovery that Fellini’s characters take in which they often find themselves trapped somewhere between heaven and earth as discussed by Donald P. Costello in his book Fellini’s Road.

In his book The Films of Federico Fellini, Peter Bondanella talks of Fellini’s departure from his roots as a maker of Italian Neorealist films. Having started in this genre as a writer for Roberto Rossili, Fellini soon abandoned his roots on his third film La Strada, by presenting characters and a plot that surpassed what was found within the neorealist genre. According to Bondanella, “Perhaps his departure from neorealist practice in rejecting the idea of film character as social type is the most important divergence from neorealist practice; but equally important is the fact that the plot and visuals of La Strada reject easy classification as a realistic story of social exploitation” (51-51). If neorealism was thought to have moved cinema away from the Hollywood “dream factory” (43) and into the streets of war torn Europe (43), then Fellini was taking it back into a dream world. According to Bondanella, “Fellini agreed with both Rossellini and Antonioni that Italian cinema needed to pass beyond a dogmatic, Marxist approach to social reality, dealing poetically with other equally compelling personal or emotional problems”(53). Hence, La Strada was born. More so then any of Fellini’s previous films, it was a parable about childlike innocence; about finding the purpose that God put you on earth to fulfill. La Strada therefore gave birth to an even newer realism; Fellini’s realism.

It was easy to see that Fellini’s films, particularly his characters, did not so much offer depictions of realism. Instead they acted as a part within Fellini’s fables. In neorealism it was believed that films should “stress social context” (Bondanella, 43). Fellini rejected this idea; his films were more like a process of working out their maker’s own spiritual life journey through the use of allegory and fable. As Bondanella writes, “More than a story, La Strada is a fable about symbolic figures, and its plot structures this origin in the fable or fairy tale” (52). The way Fellini’s films are structured, La Strada, Nights of Cabiria, and La Dolce Vita in particular, is that they both begin and end at the sea; they come full circle back to their beginnings. For Fellini, especially as a Roman Catholic, this book ending represented a new beginning for his characters, a chance for spiritual redemption. Bondanella offers this explanation: “Rather than viewing the world from the perspective of class struggle or class conflict, La Strada embodies a profoundly Christian emphasis upon the individual and the loneliness of the human condition” (54). In using the image of the sea, Fellini is showing the viewers that his films are not about the underpinnings of a Marxist society, but rather the choices of an individual journey; the journey away from the birthplace and back, in an attempt to find, not a place within society, but a place within the spiritual universe. In Fellini’s reality, faith takes precedence over class.

Besides the road, there are two other images that constantly appear throughout Fellini’s body of work, usually appearing in conflict with one another. One of these images is that of the circus: a place of spontaneity and life, a place where it is the norm to think the unthinkable, to believe the unimaginable. To Fellini, the circus was a place of great imagination and invention. Edward Murray in his book Fellini the Artist states that “Where the circus…appears directly in his pictures, it stands as a metaphor, a device for revealing life as a funny- sad experience with cosmic significance” (232). Indeed, to Fellini, a man who liked to create his own reality, whether it was derived from his own life, or a life he had made up, the circus was a place of unending imagination.

The circus however was not the only part of Fellini’s realism. Fellini was a director who was constantly trying to work out the dual nature of reality, trying to blur the lines between the “real and the ideal” (Murray,234). Thus Fellini’s films present a reality that was not the same one that the neorealists dealt with. Rather it was one that was Fellini’s itself, a world in which imagination and performance were held in the highest regard, and thus the circus was always in constant conflict with the church. In reality, the church reined supreme in Rome, and this is why it was under constant comparison to the circus. As Murray helps us understand, Fellini was constantly trying to show us life’s poles, that every road has two paths, more importantly, “life as it is, and life as it ought to be” (234). Throughout his films Fellini constantly presents the audiences with two versions of life. The life that we have, which is one of banality, hurt and sorrow, and most importantly of displacement, and the life that we could have if we lived a little better, were a little more loving, and lived with a little more direction; a true dolce vita.

For Fellini the circus offered direction where the church did not. The church to Fellini “(S)tands for an inauthentic way of life, since it tends to thwart man’s expansive capacities” (Murray,30). The reality of the church was that it presented a strict way of life, a doctrine that was to be accepted and lived by. To Fellini the church undermined an individual’s imagination. The church was not concerned with poles. In Fellini’s eyes, the church only saw one way to live; their way, which Murray helps to illustrate in pointing out that “(H)is attitude towards the Church is a rebellious one” (31). Murray goes on to state that this is because “(T)he polarities that distinguish the Fellinian universe guarantee the director a sufficiently rich assortment of themes with which to capture the interest of the intelligent viewer, who invariably likes to be shown the different sides of every experience”(31). Alas, the church and the circus need each other. If the church only shows us one side of what life should be, Fellini needed the circus to show us the other.

Although Gesulmina in La Strada never comes into such direct conflict with the church as Fellini’s later characters such as Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1957) or Marcello (La Dolce Vita, 1960) would, we are still able to get a glimpse of how the circus functioned in Fellini’s realism. The poles in this film revolve around the circus and the world outside which in a way, mimics the reality of neorealism; life in a working class society. We see that Gesilmina is unhappy to hear of her sister’s passing and that she will have to take her place alongside Zampano and his traveling circus-like act. Yet it is when she is performing that reality slips away and for a brief moment, she is happy. The circus is able to strip reality away and offer hope when all seems hopeless. That’s the brilliance of Fellini’s realism, when life seemed to be going bad, there were fantasy places like the circus, or on a larger, more metaphorical scale, Fellini’s films themselves, to escape to in order to find comfort and happiness.

Coming back to the metaphor of the road, in his book Fellini’s Road, Donald P. Costello states that “Throughout all his films, Fellini is concerned with the road of life” (5). There is no doubt that one of the main themes throughout all of Fellini’s films is that of a spiritual journey, of a character who is caught between Heaven and Earth, who must journey down this road in order to find their placement in life. To reinforce this idea, Costello states: “Both thematically and formally, a Fellini film is a journey toward discovery of the essential self” (5). In the director’s own words: “(E)ach time I am telling the story of characters in quest of themselves, in search of a more authentic source of life, of conduct, of behavior, that will more closely relate to the true roots of their individually” (Fellini in Costello, 2). This journey usually must be taken, as Fellini’s characters often find themselves trapped between the earth and the sky. In La Strada, The Fool represents the sky and Zampano the Earth. Similarly 8 ½ finds it’s main character Guido being held to earth only by a rope around his foot, and in La Dolce Vita, Marcello is caught between a flying statue of Jesus and a monster from the sea.

In a similar sense, Costello breaks down the three characters of La Strada into a trinity which involves The Child of the Sea (Geselmina), the Spirit of the Sky (The Fool) and the Man of Earth (Zampano) ( 23, 18 and 27 respectively). These three elements, in one form or another, come to represent the spiritual journey that Geselmina, Cabiria, Marcello, Guido, etc, will all have to take along their road to spiritual fulfillment. It is important to note that each of these journeys end with their character’s finding their way back to be offered the possibility of redemption at their place of origin: the sea. For Fellini the sea represented several things. It represented the innocence of youth, the feminine and most importantly, the beginning of life (Costello, 6). It is at the sea in La Strada where Geselmina, although dead, can complete the purpose of her spiritual journey, which was to help Zampano to understand his loss and find redemption on the beach. In a way, although tragic on the surface, the final scene in which Zampano cries on the beach is a baptism for this man, a rebirth which offers a way to start over on a new path of life. This is ultimately the possibility that Fellini presents all of his characters with at the end of his films, some of whom accept it (Cabiria) and some who don’t (Marcello).

Fellini’s films constantly presented a spiritual journey down the road of life. Through three specific texts based on the director’s work, we can see that this journey stood in constant contrast with the Italian Neorealism movement, which presented characters trying to find their place within a Marxist society. We also see that Fellini was constantly contrasting the church with the circus to show us how he viewed the importance of life and imagination. His films also constantly showed the struggle of a character who was stuck somewhere between Heaven and Earth. Through all of these themes and ideas, Fellini was able to create a realism that was not the one that was shared by his audience but one that existed all to himself: a Fellini realism.

Labels:

8 1/2,

Federico Fellini,

La Dolce Vita,

La Strada,

Nights of Cabiria

Justify Your Shitty Taste: Knowing

Question is: was our losing the keys just a random hiccup of the brain or part of a preordained destiny? How easy it is to take for granted that stopping to tie a shoe, turning left instead of right, looking down instead of up, etc. could potentially be the difference between life of death. But whose terms do we really operate on, ours or the universes?

Think before deciding. If life is random than we simply go through the motions until our death and everything is meaningless, but if life is predetermined, free will is an extinct commodity, ultimately thwarting many religious and political debates as every suicide or abortion were already planned by a being greater than our human capacity could ever comprehend. If I’m writing this because it’s my destiny, then you’re reading it for the same reasons.

These are the things that entered my mind while watching Alex Proyas’ Knowing, which does something rare for this day and age: it manages to be both a stunning entertainment and unimaginably intelligent. It’s a rare science fiction film that doesn’t compromise its integrity by throwing it away to spectacle.

Knowing is a film that asks its audience to sit, watch, listen and, most importantly, pay attention while it spins its tale of destruction. So rare is it that a film stretches itself without apology to the very limits of its narrative possibilities (even if that means into the realms of the preposterous) these days that it is mistaken as bad filmmaking. Knowing is a film that, like all great science fiction, knows that art is a vehicle for raising questions, not giving them arbitrary answers.

Nicholas Cage stars as John Koestler, a professor of astrophysics who believes that the universe is comprised of a series of random events after his wife was killed while out of town when her hotel catches fire. John has a young son named Caleb who receives a mysterious paper covered in random numbers when a ceremony is held at his school to unlock a time capsule buried fifty years prior. The paper was written by the disturbed Lucinda Embry whose assignment for the capsule was to draw a picture of how she though the future would look.

What John slowly begins to realize after analyzing the paper is that the numbers form a code, predicting all of the disasters that will precede the end of the world. The numbers provide the date of the tragedy, the body count and the coordinates of the location. According to the code there are three disasters left before the world ends, all three of which, visually speaking, set a new standard in what special effects can achieve.

As John becomes obsessed with the code he desperately tries to track down the late Lucinda’s daughter for answers. Meanwhile, Caleb begins being visited by strange, darkly cloaked men whose constant whispers in his head also afflicted the young Lucinda and seem to be telling him something. Is Caleb a messenger for God or a victim of his own psyche?

Proyas, whose Dark City was also a (very different) masterpiece about the nature of human existence, takes what could have easily been a mindless entertainment (as the trailers make it out to be) or an absolute train wreck (as it would have been under original helmer Richard Kelly) and infuses it, not only with mind bending special effects, thrilling chases, and gripping storytelling, but with complex and intelligent images that are constantly contradictory to one another. At its heart Knowing is a constant battle between science and theology, the possible and the divine, the physical and the metaphysical, and so on. It, like The Dark Knight and Watchmen will be the central focus of many scholarly essays to come

The brilliance of the film, and arguably most of its suspense, lies in how it is never quite willing to tip the scales in favor of one side. I dare not even hint at the outcome of the story, which is next to impossible to predict, but to draw attention to how even the circumstances that govern it cannot simply be pegged down to that of the scientific or the Biblical. Can it be that one becomes real, or at least possible, in light of the other? Or will they constantly cancel each other’s integrity out: the Bible explaining everything that science can’t and science explaining everything the Bible can’t? What does that say about the nature of our existence? It may be easy to write the conclusion of this film off as improbable, but the debates it raises are real and, like all great science fiction, it believes in them down to the very last frame.

It’s truly rare these days to find a film whose vast intelligence is not confined to the insufficient demands of the running time, nor whose ideas are limited to the images on screen. A film whose musings slowly slip from the screen and out into the world because they are larger and more important than just getting a story from beginning to end. A film that is, to top it all off, one hell of a thrill ride. Yes, films like that are rare. Knowing is exactly one of them.

Labels:

Alex Proyas,

Justify your shitty taste,

Knowing,

Nicholas Cage

Sunday, August 7, 2011

A Call To All Bloggers: Justify Your Shitty Taste

There's a metal magazine called Decibel which I've never read before but their content is always linked on a a popular metal blog called Metal Sucks that I read all of the time.

One of my favourite columns that Metal Sucks always links to is "Justify Your Shitty Taste" in which a reviewer picks an album out of a bands catalogue that is considered by the masses to be a huge embarrassment or misstep in their career and writes a piece justifying why it is that they actually like it.

So, in order to rip off a good idea when I see one, I'm putting out a call to all movie bloggers to justify their own shitty taste.

It's simple: sometime this week, pick a movie that you like that the vast majority of critics and fans have hated and tell us why you think you are right and why everyone should give this movie a second chance.

Then come back here, post the link in the comments section and at the end of the week I will gather all of the links and post them in one place for everyone to enjoy. Let's make this fun and give people a reason to go back and rethink movies that got to critical brush off the first time around.

One of my favourite columns that Metal Sucks always links to is "Justify Your Shitty Taste" in which a reviewer picks an album out of a bands catalogue that is considered by the masses to be a huge embarrassment or misstep in their career and writes a piece justifying why it is that they actually like it.

So, in order to rip off a good idea when I see one, I'm putting out a call to all movie bloggers to justify their own shitty taste.

It's simple: sometime this week, pick a movie that you like that the vast majority of critics and fans have hated and tell us why you think you are right and why everyone should give this movie a second chance.

Then come back here, post the link in the comments section and at the end of the week I will gather all of the links and post them in one place for everyone to enjoy. Let's make this fun and give people a reason to go back and rethink movies that got to critical brush off the first time around.

Monday, August 1, 2011

Captain America

Captain America, I suppose, has to be admired on some basic level, as all film with a certain degree of competence deserve to be admired, in which one can appreciate the acting, the direction, the visual aesthetic and the action. It’s a complete package with the bow on top. Nothing less and not much more either.

I guess one can primarily admire it for it’s having a real human character at the centre of it. Most comic book movies these days are animated video games with human faces that pop up amidst the computer generated effects. Captain America has a lot of that kind of stuff too but it also has a little comedy and a little heart as well. It has, above all, a hero who provides a human centre for the story; one who you could get behind. Not enough to put it in line with Iron Man or The Dark Knight to be sure, but enough to safely say, without much irony, that it’s better than, say, the Transformers movies. Faint praise is still praise, no?

For those who don’t know, Captain America is about Steve Rogers (Chris Evens) a small awkward kid who wants nothing more than to serve in the army and fight for his country in the war. He enlists under several different names but with a list of ailments a mile long is denied at all of them. The kid has guts and heart though and isn’t afraid to take a back alley beating or two from the local bully when need be.

Trying to enlist one final time at the World Fair where Howard “father of Tony” Stark (Dominic Cooper) unveils his first hover car, Rogers is discovered by Dr. Erskine (Stanely Tucci), a German scientist who fled to America away from Johann Schmidt aka Red Skull (Hugo Weaving), a ruthless Nazi who believes he can harness the power from some glowing cube in order to rise above Hitler and win the war.

Erskine, wanting to use this unexplained power for good, selects Rogers as a test subject much to the cynicism of Colonal Chester Phillips (Tommy Lee Jones doing Tommy Lee Jones) and the admiration of potential love interest Peggy Carter (Haley Atwell). Regardless, once injected with this mysterious power, Rogers exits the experiment a muscle bound hunk with amazing physical power.

He is first put to use as an American hero selling war bounds but once he learns that his friend has been captured behind enemy lines and presumed dead, Captain America single handily goes behind enemy lines, infiltrates Red Skull's operation, saves the men and sends Red Skull into a rage.

All of this is all fine and dandy and made with style and humour. Director Joe Johnson does a good job of creating the look and feel of an old newspaper serial of the time and he takes special care of ensuring that there is a human story amidst all the special effects and the action.

However, if there is any problem with this concept it is that, while stacked up against other Marvel comic book films that have defined the genre such as Spider-Man or Iron Man, Captain America simply doesn’t have much personality. Evans in the lead role doesn’t have the charisma or charm to pull off Rogers' sweet naivety even after he becomes Captain America, and Weaving, a great character actor in his own right, isn’t given the kind of depth that goes into making a great villain, especially one as iconic as Red Skull.

And that’s Captain America: a film that is, in these summers of excess, better than most, but not nearly enough to achieve anything close to memorable. Comic book movies used to be based on relatable characters with human traits put into a narrative that doesn’t cross real life, but runs in such a way parallel to it that it’s pointed yet simple messages can jump across the divide and connect with us. Captain America sets up all the elements to get the first thing right but doesn’t come close enough to approaching the second. Too bad.

I guess one can primarily admire it for it’s having a real human character at the centre of it. Most comic book movies these days are animated video games with human faces that pop up amidst the computer generated effects. Captain America has a lot of that kind of stuff too but it also has a little comedy and a little heart as well. It has, above all, a hero who provides a human centre for the story; one who you could get behind. Not enough to put it in line with Iron Man or The Dark Knight to be sure, but enough to safely say, without much irony, that it’s better than, say, the Transformers movies. Faint praise is still praise, no?

For those who don’t know, Captain America is about Steve Rogers (Chris Evens) a small awkward kid who wants nothing more than to serve in the army and fight for his country in the war. He enlists under several different names but with a list of ailments a mile long is denied at all of them. The kid has guts and heart though and isn’t afraid to take a back alley beating or two from the local bully when need be.

Trying to enlist one final time at the World Fair where Howard “father of Tony” Stark (Dominic Cooper) unveils his first hover car, Rogers is discovered by Dr. Erskine (Stanely Tucci), a German scientist who fled to America away from Johann Schmidt aka Red Skull (Hugo Weaving), a ruthless Nazi who believes he can harness the power from some glowing cube in order to rise above Hitler and win the war.

Erskine, wanting to use this unexplained power for good, selects Rogers as a test subject much to the cynicism of Colonal Chester Phillips (Tommy Lee Jones doing Tommy Lee Jones) and the admiration of potential love interest Peggy Carter (Haley Atwell). Regardless, once injected with this mysterious power, Rogers exits the experiment a muscle bound hunk with amazing physical power.

He is first put to use as an American hero selling war bounds but once he learns that his friend has been captured behind enemy lines and presumed dead, Captain America single handily goes behind enemy lines, infiltrates Red Skull's operation, saves the men and sends Red Skull into a rage.

All of this is all fine and dandy and made with style and humour. Director Joe Johnson does a good job of creating the look and feel of an old newspaper serial of the time and he takes special care of ensuring that there is a human story amidst all the special effects and the action.

However, if there is any problem with this concept it is that, while stacked up against other Marvel comic book films that have defined the genre such as Spider-Man or Iron Man, Captain America simply doesn’t have much personality. Evans in the lead role doesn’t have the charisma or charm to pull off Rogers' sweet naivety even after he becomes Captain America, and Weaving, a great character actor in his own right, isn’t given the kind of depth that goes into making a great villain, especially one as iconic as Red Skull.

And that’s Captain America: a film that is, in these summers of excess, better than most, but not nearly enough to achieve anything close to memorable. Comic book movies used to be based on relatable characters with human traits put into a narrative that doesn’t cross real life, but runs in such a way parallel to it that it’s pointed yet simple messages can jump across the divide and connect with us. Captain America sets up all the elements to get the first thing right but doesn’t come close enough to approaching the second. Too bad.

Labels:

Captain America,

Chris Evans,

Iron Man,

Joe Johnson,

Spider-Man,

Tommy Lee Jones

Expecting Good Criticism

The expectation argument is the worst form of criticism out there. I take that back. As someone who has written extensively on the nature of criticism as a practice and an art form unto itself within this space I can more accurately say, it's not even criticism at all. It's just plain lazy as well. It's a cheap and quick excuse to not give a film the time and energy to understand what it did and how you interacted with it, and it's also a form of passing the buck because, of course, if so many other people wouldn't have liked it so much you could have liked it more.

Arguing expectations is like drawing lines in the sand and seeing how the tide comes in. If you draw the line close to the water you don't expect much of the tide and if your line gets washed away your expectations have been exceeded. You can do the same in reverse. The point is is that criticism is not drawing lines in the sand. It's about relating to the water and understanding it's movement and drawing a line based on your feelings and findings in which the water can meet, and balance has been achieved.

Because, to get to the point of all that, criticism is about you in relation to the movie. Expectations are about you in relation to what you've heard. If a movie is better than you expected that doesn't make it a good movie and to expect a movie to be better than what you felt it was does not make it bad. To do this is to judge, as Roger Ebert always argued against, the movie you wanted to see and not the one that has been put in front of you.

Of course justifiable expectations will always exist. When I watch a new Ingmar Bergman movie that I haven't seen I expect it to be great as Bergman has a track record for making great movies. But if one happens to not meet those expectations this does not mean the film is to be thrown away, considered lesser Bergman, mean it deserves a bad review or any such variable. What it means is that I have some thinking to do. If I watched the Seventh Seal and didn't agree with the critical majority that it's one of the best films ever made the problem is with me not the film and it's up to me to reflect back and understand why this film has been deemed to be such, and in most cases, with both personal and analytical reflection, the truth will reveal itself eventually.

This happened this summer with two films. Cars 2, which was better than the original, was spoken down to because people expect more from Pixar while Transformers 3 was, for some, given a free pass because they weren't expecting it to be better than the awful second film.

Of course, expectations will never be able to be totally managed. Films accumulate history and reputations almost instantly, that will grow and change over time. Lesser critics maybe don't trust their literary voice enough to to say the same thing as everyone else but in a compelling and personal way and the truth of great cinema almost never reveals itself immediately. It requires quite time to sit and reflect and to understand exactly what a movie has done and how that has effected you, because, as I've argued many times before, there is a strong difference between what you like and what is good (the best criticism existing between the two and tying them together).

That is, after all, why we read criticism in the first place. We want to know how a movie effected it's viewer in an intelligent and/or emotional way, not how it fell in line in relation to their expectations. I expect more from critics.

Arguing expectations is like drawing lines in the sand and seeing how the tide comes in. If you draw the line close to the water you don't expect much of the tide and if your line gets washed away your expectations have been exceeded. You can do the same in reverse. The point is is that criticism is not drawing lines in the sand. It's about relating to the water and understanding it's movement and drawing a line based on your feelings and findings in which the water can meet, and balance has been achieved.

Because, to get to the point of all that, criticism is about you in relation to the movie. Expectations are about you in relation to what you've heard. If a movie is better than you expected that doesn't make it a good movie and to expect a movie to be better than what you felt it was does not make it bad. To do this is to judge, as Roger Ebert always argued against, the movie you wanted to see and not the one that has been put in front of you.

Of course justifiable expectations will always exist. When I watch a new Ingmar Bergman movie that I haven't seen I expect it to be great as Bergman has a track record for making great movies. But if one happens to not meet those expectations this does not mean the film is to be thrown away, considered lesser Bergman, mean it deserves a bad review or any such variable. What it means is that I have some thinking to do. If I watched the Seventh Seal and didn't agree with the critical majority that it's one of the best films ever made the problem is with me not the film and it's up to me to reflect back and understand why this film has been deemed to be such, and in most cases, with both personal and analytical reflection, the truth will reveal itself eventually.

This happened this summer with two films. Cars 2, which was better than the original, was spoken down to because people expect more from Pixar while Transformers 3 was, for some, given a free pass because they weren't expecting it to be better than the awful second film.

Of course, expectations will never be able to be totally managed. Films accumulate history and reputations almost instantly, that will grow and change over time. Lesser critics maybe don't trust their literary voice enough to to say the same thing as everyone else but in a compelling and personal way and the truth of great cinema almost never reveals itself immediately. It requires quite time to sit and reflect and to understand exactly what a movie has done and how that has effected you, because, as I've argued many times before, there is a strong difference between what you like and what is good (the best criticism existing between the two and tying them together).

That is, after all, why we read criticism in the first place. We want to know how a movie effected it's viewer in an intelligent and/or emotional way, not how it fell in line in relation to their expectations. I expect more from critics.

Labels:

Expectations,

Ingmar Bergna,

The Seventh Seal,

Transformers

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)